It’s always fun to trace the chain of Chinese whispers between primary research and scary news stories about the ravages of climate change. Many BBC science stories are particularly easy to trace back to source, based as they are on a single scientific paper, from which they are separated by only a single press release. But even when the whisper chain is a short one, there is plenty of room for the distortion of sobre science to alarmist headline, especially when the press release contains everything you need for the job. So it was with the BBC’s ‘Bid to aid daddy longlegs numbers’ published on Thursday:

Climate change is killing off cranefly and in turn threatening the survival of upland wild bird species that feed on them, RSPB Scotland has warned.

The Telegraph also reported the story:

Daddy longlegs decline could spell extinction for golden plover

So did the Daily Mail, which isn’t even supposed to believe in this new-fangled climate change business:

Warmer summers ‘killing off daddy long legs and beloved British birds’

And Science Daily:

Drop In Daddy Long Legs Is Devastating Bird Populations

All the stories drew entirely from a press release issued by RSPB Scotland, which they have simply condensed and bolted on their own introduction and headline. (Science Daily also spliced in an extra quote from a co-author of the research paper). Here’s the headline of the presser:

Warmer weather pummels plovers

Craneflies – better known in the UK, at least, as daddy longlegs – are gangly insects that appear en masse in temperate regions for a few weeks in spring, providing a bonanza food source for breeding birds and other predators. Judging by the news stories, climate change is killing them off by drying out the soil in which their larvae live, which is in turn killing off the birds that rely on them.

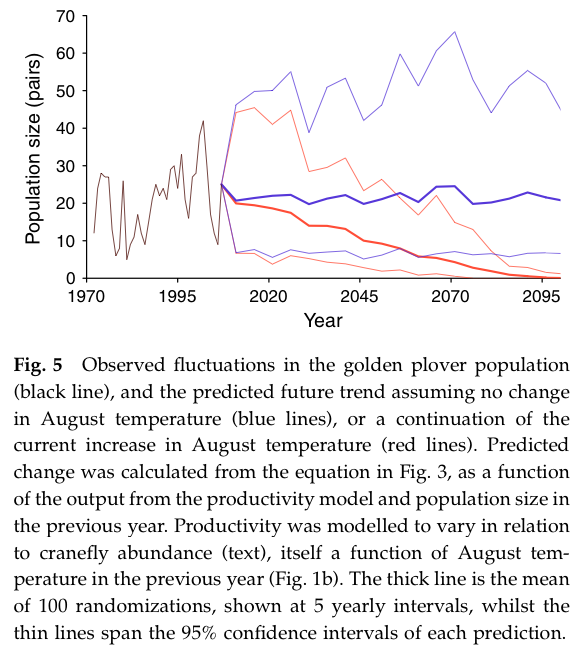

But according to the research paper, published in the journal Global Change Biology, it is far from clear that golden plovers are even declining, let alone being ‘killed off’, ‘pummeled’ or ‘devastated’, as shown in the paper’s Figure 5:

The data represent just a single, small population. But neither is there much evidence that golden plovers are undergoing a national, European or global decline. Lead author of the paper, Dr James Pearce-Higgins of RSPB Scotland, confirmed this when we spoke to him on the phone.

The population studied by Pearce-Higgins and his colleagues sits on the southern edge of the species’ range in the English Peak District. This was by design, in that the intention was to examine how global temperature rises might affect species distributions. While evidence is accumulating that many species expand their ranges northwards in response to a warming trend (in the Northern Hemisphere), evidence for predicted contractions at the southern limit of species’ ranges is sparse. But even in what might be expected to be a particularly sensitive population, there is no downward trend in plover numbers over the last 35 years, despite a local rise in mean August temperatures of 1.9C over that period.

That is not to say, however, that temperature rises are not having an effect on the population. Pearce-Higgins et al have developed a model that does seem to explain much of the variation in plover numbers over the 35-year period. The model integrates previous work by the group, which found that plover mortality rises in cold winters, with new data showing that high August temperatures kill off cranefly larvae leading to fewer adults emerging the following spring when the birds are feeding their chicks. So, rising temperatures are a double-edged sword for plovers. Mild winters increase survival, but hot summers reduce breeding success. The model suggests that there might have been a switch in the relative importance of these two effects in recent years, with spring food availability becoming a more important determinant than winter temperature of population size.

There remains, of course, a lot of unexplained variability in the system, and Pearce-Higgins is reticent to attribute any short-term population fluctuations to specific effects:

From about the mid-’90s to mid-2000s, when the time series stops, there’s actually – although we don’t put this in the paper – there’s actually a significant decline in golden plover numbers […] I guess I was being cautious really, in terms of attributing the decline to what’s going on, particularly as, if you look across the whole of the UK, there isn’t much evidence of a golden plover population decline, and I’m very well aware that lots of other factors are affecting their population […] If you take the trend from the mid-90s through to when we finish about 2005, there is a decline there, but obviously that’s an arbitrary cut-off.

So, all the news stories – and, indeed, the RSPB’s own press release – are wrong to suggest that climate change is reducing plover populations. While they all treat the issue in the present tense, as if golden plovers are being devastated by climate change in the here and now, the only evidence of population decline presented by paper comes from the application of the model to future population trends.

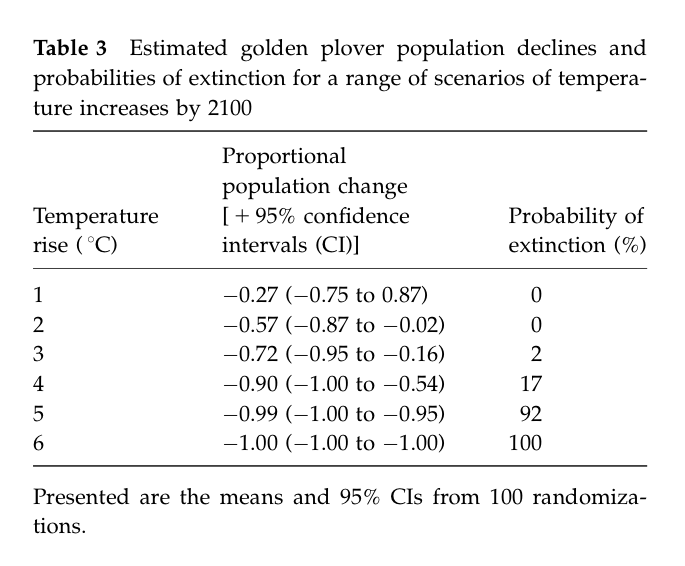

The researchers take the 1.9C local temperature rise over the past 35 years and extrapolate it over the next 100 years. The resulting rise of 5.2C above the 1971-2005 mean would, according to their model, result in a 96% chance of extinction of the population. A 1.9C local rise in August mean temperatures would seem very large, however, when global temperatures have increased by 1C over the past century, and it’s certainly much bigger than the rise in temperature experienced by central England over the same period.

The researchers also apply their model to a range of other temperature scenarios:

In other words, things have to get pretty warm before even a small population on the edge of the species’ range starts to feel the heat. And yet it is only the extrapolation of the 1.9C rise that makes it into the press release and, therefore, the news stories.

Not only have news reports confused current declines with possible declines in the future, but they deal only with an apparently unrepresentative worst-case scenario, and they apply data from a single population at the southern extremity of the species’ range to the species as a whole to announce that a species that isn’t even declining is being driven to extinction.

Given that all the news coverage of the paper was based almost verbatim on the press release, it is perhaps surprising that Pearce-Higgins is happy with how the RSPB presented the research:

I don’t think the press release is particularly misleading really

‘That’s the challenge’ he says,

to try to get across what is quite a complicated message, but with an important underlying message, in a way that is acceptable to the media, but that also does justice to the science.

Readers can make up their own minds whether the RSPB press release does justice to the science. But it certainly seems to have been acceptable to the media, who didn’t need to look any further to get their alarmist climate stories. One particular quote in the RSPB press release proved particularly attractive, being used by the BBC, Telegraph and Daily Mail. It’s from Pearce-Higgins:

This is the most worrying development that I have found in my scientific career to date.

Perhaps that’s what he means by the ‘important underlying message’.

Excellent. Thanks for making the effort to ferret out the truth.

With that said, it’s really a tragedy that we can no longer trust the scientific community and the main stream press to share and report science research in a non-agenda manner. I’m sure I speak for many others when I say I no longer trust any source of information that claims a crisis is in the making, or a disaster awaits in the very near future. Almost every single reported instance of such imminent disaster has proven to be false. The scientists and reporters have lost all credibility and it’s been entirely self-inflicted.

perhaps golden plovers will decline more in line with the models now that the RSPB backs wind turbines

I am a bit confused.

The daddy long legs are being killed off at Forsinard, Caithness, in the very North of Scotland, yet the plover population that is declining is in the English Peak district?

So are the Peak district plovers the same Caithness plovers?

RSPB took over Forsinard in the 1990’s.

http://www.rspb.org.uk/supporting/campaigns/flowcountry/future.asp

So what have they done to kill off the daddy long legs?

The BBC links this event with climate change.

What a change in the BBC attitude since 2006.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/5386164.stm

BBC: “The UK is in the grip of an explosion of daddy longlegs – or crane flies as they are otherwise known – because of the combination of a hot summer followed by heavy rain showers and a dry, warm September.”

Another very good article, and a fine example of how the potent alchemy of the media is able to transform a molehill of fact into a looming mountain of probabilities and runaway generalisations.

Basically the upshot to this story of pummelled plover productivity is that there might be a future decline in golden plover numbers in certain peatland areas, due to a decline in the number of cranefly larvae (not just any craneflies but the small peatland variety) which are affected by peatland drying out in hot summers.

Plenty of questions come to mind: The time series stops in the mid 2000s – almost half a decade on, has the run of warm summers continued? If not, what has happened to cranefly numbers – have they rebounded? Has anyone been up there to check since 2005? What happened to the peatlands/craneflies/plovers in earlier warming periods (e.g., during the first part of the 20th century, or the 1730s?) and what happened to them when it became cooler? Could it be that whenever there’s a run of hot dry summers, the craneflies reduce in numbers and the plovers have a hard time, but when the conditions are reversed and we have a string of cool, wet summers (1950s? 1960s?), the craneflies recover and the birds feeding on them also do well?

In a nutshell, could it be that over the decades (and centuries) conditions fluctuate and that what we see is always basically a snapshot?

Teares, I just had a look at the link you provided to the Forsinard article. Two paragraphs stood out immediately:

“Home to a rich variety of wildlife, including many beautiful and fascinating birds, this fragile habitat has been badly damaged in recent years, through misplaced forestry activity and artificial drainage.

The Caithness and Sutherland peatlands, also known as the Flow Country, comprise the largest area of blanket bog in the UK and possibly in the world

The trees dry out the peat, changing the habitat and destroying its value for birds and other wildlife. These peat deposits, which can be 30 feet deep, took up to 8,000 years to accumulate. Once dry, the crumbling peat is blown away by the wind gone forever.”

How much of the decline of craneflies, birds etc., in these areas can be attributed to changes in land use, I wonder?

Alex Cull

I used to travel to Thurso, once or twice a year. The Flow Country was always bleak, grey, cold, wet and miserable, not my favourite place in Scotland.

Sure some trees were planted, but in small clumps in thick concentrations; some peat was being removed on an small industrial scale.

As far as the peats drying out and blowing away, well we are talking about the North of Scotland. Drying out is not a problem.

The RSPB at Forsinard have also made changes to the land use with their reserve and track.

http://www.rspb.org.uk/reserves/guide/f/forsinard/index.asp

And what can we see at the nature reserve?

“Summer is the time to come, when golden plovers, hen harriers and green shanks breed.”

That list surely did not include Golden Plovers?

“Why not come on a guided bog walk to get up close to the fascinating flora and fauna?”

If you do then make sure you are covered in midge repentant, you’ll need it. That should see off a few crane flies as well.

Teares, I haven’t been to the Flow Country but we did have some holidays in the Highlands when I was a child. We had some great days there, but I remember the rain and the midges. Yes, it would be interesting to see what changes the RSPB are themselves making to the landscape.

Teares,

Thanks for the Forsinard link. In fact, Forsinard isn’t part of the study. The long-term cranefly data (if you can call 10-11 years long-term) were from two other Scottish sites, one on the East coast, and the other in the Borders – ‘the only available long-term data on the abundance of craneflies in the United Kingdom uplands’, according to the paper. So it’s interesting that Pearce-Higgins mentions Forsinard in the presser, especially given the significant effect of drainage ditches there. The researchers don’t mention in the paper whether there are drainage ditches at the plover sites. We like to think that they would have done had there been any, but it’s an intriguing possibility that they might be measuring the effects of land management practices rather than temperature trends.

We probably should have mentioned in the post that the data don’t show a decline per se in cranefly numbers – just a negative correlation with maximum August temperatures. Which makes the news reports doubly wrong, in that neither of the ‘declining’ species are actually declining.

Thanks Editor

The BBC article made it clear that crane flies are in the decline and that ditches are being blocked at Forsinard, Caithness. Implication being that filling in the ditches will save the crane flies.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/highlands_and_islands/7963088.stm

“RSPB Scotland said a dramatic decline of the insect could lead to localised extinctions of some birds.

Ditches are being blocked at Forsinard, Caithness, in a bid to help the larvae.”

That is what the BBC have reported to me and everyone else in Scotland. So no crane flies no birds; localised birds become extinct.

Yes yes yes Extinct, like the Dodo, never to be seen again on planet Earth.

Dr James Pearce Higgins, of RSPB Scotland, said: “For example, by blocking drainage ditches on our Forsinard reserve in the North of Scotland we hope to raise water levels and reduce the likelihood of the cranefly larvae drying out in hot summers.”

(I remember being in Orkney when the August temperature went up to 61F. “Heat Wave hits Orkney”, said the Orcadian newspaper.)

Hot summers in Caitness are in the 50F if you are lucky.

Editor your posting says; “The long-term cranefly data (if you can call 10-11 years long-term) were from two other Scottish sites, that the East coast, and the other in the Borders”

Who mentioned the Borders?

The original BBC article says Caithness.

Also ‘the long-term data on the abundance of craneflies in the United Kingdom uplands’ Upland; Forsinard is 150ft above sea level, that is now considered uplands?

I am even more confused?

RSPB are studying Crane flies in the South East of Scotland and filling in ditches in the far North of Scotland where the upland summers are hot.

Editor, just said to my wife that we will go to Caithness this summer instead of Naples/Florida.

I am away down to buy her some flowers.

In the graph, actual plover levels appear to have dropped from 28 to 8 pairs in just a few years from the 1970s (and then back up again and down etc). Rather than doing apocalyptic forecasts why don’t they try to explain this variation first.

They they appear to make the (sadly common) logical error in assuming that any recent drops in cranefly populations are/or will be entirely due to climate change and don’t exhibit a natural fluctuation cycle like the plover’s.

Finally, as you acknowledge, Flat Earth News is well in action here – sensational distortion of distorted press releases – churnalism.

Sustainability seems to be to process of clinging to artificially defined ‘natural’ levels and then rallying against nature’s actual changes and cycles. It’s all so Cnutian.

Luke,

We wouldn’t want to speak for the scientists, but the population decline in the early ’70s is likely ‘explained’ by a spate of cold winters at the study site, which kills off adult birds. The researchers’ model takes this into account as well as well as the effect of high August temperatures.

Of course, just because the model describes much of the variation, it doesn’t follow that the model is correct. It might well turn out that they’ve hit lucky. But that is a matter for scientists to work out. We tend to steer clear of debunking scientific papers here. We’re not qualified for the job. What interests us is the way scientific information is presented beyond the ivory tower – by the media and by the scientists themselves. That said, we wouldn’t be at all surprised if there is a reluctance among the scientific community to scrutinise research that paints such a convenient picture. But that’s a different matter.

Oh come on guys – you’re not allowed to suggest that cold can be bad:-)

They could at least plot T against pop for that area to test this. And why is cold bad – what variation was there in cranefly populations, other foodsources, water or predators etc.?

Wonder what the Scottish plover population was 12,000 years ago? (Pre-industrial, pre-holocene)

But you’re right it’s the spin amplification of this that’s most worrying. Positive media feebacks and runaway climate reporting. I’m starting to believe this is man-made but not in the way the warmers think.

The golden plovers are being killed by the RSPB’ own policies: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/earthcomment/charlesclover/3340477/RSPB-accused-over-birds-on-flagship-reserve.html at least in part.

Got this from Numberwatch.

The golden plovers are being killed by the RSPB’s own policies: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/earthcomment/charlesclover/3340477/RSPB-accused-over-birds-on-flagship-reserve.html at least in part.

Got this from Numberwatch.

A similar scare story has just emerged in the media re migrating birds.

Here’s the story in the Telegraph:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/wildlife/5152751/Migrating-birds-have-to-fly-250-miles-further-due-to-climate-change.html

And here’s Lubos Motl’s fine analysis of it in The Reference Frame:

http://motls.blogspot.com/2009/04/bird-migration-and-warming-example-of.html

Re the Telegraph story, just look at the wording. The headline is “Migrating birds have to fly 250 miles further due to climate change.” Absolute certainty there, and it’s in the present tense – all true and happening right now! It’s when you start reading the rest of it that you encounter all the coulds, woulds and likelys.

“Sober science to alarmist headline.” Again.