Why Do Environmentalists Hate Liberty?

Warning… This is a VERY long post! You may want to skip straight to the conclusion, labelled in bold.

This blog has always been interested much more in questions about what environmentalism is, rather than in the scientific claims made by environmentalists. One could argue forever about what lines on charts ‘say’ without ever becoming the wiser about what to do about them. The argument here is that in order to know what ‘science says’, you have to know what you have told it, and too much telling has been smuggled into scientific claims about the environment.

The problem is, environmentalism is rarely presented as a political idea in the way that, for example, the nature of capital has been discussed between Smith, Marx and their descendants. Environmentalism’s moral argument tends these days to come from projecting some trend or other into the future, to create imperatives in the present: if you drive your 4×4 today, your children’s’ children’s’ children’s’ children will suffer and die. Another form of environmentalism that looks less like blackmail, but which is consequently less useful to political campaigning is the notion that there is value in the natural world, independently of our being there to value it: that a river might have intrinsic rights to be as it is, free from our interference. The latter form of environmentalism is more nuts, but it is perhaps more honest.

The blackmail form of environmentalism leaves very little room for nuance, which is why contemporary environmentalism hasn’t really needed philosophers or political thinkers to shape the movement. ‘Science’ does the heavy lifting that, in other movements, have been done by branches of philosophy, such as ethics, and metaphysics. All it needed was scientists to make their discoveries, and for a few journalists to announce “it’s worse than previously thought”. Once you know that the End is Nigh, (or nigh enough), all you need to do to do the right thing is stop it. This is a shame, because it’s reduced debates about the environment to debates about lines on charts and the circumstances of their creation. The climate debate has descended to science. It hasn’t had any light shone on it by science.

A few philosophers have waded into the debate, however. Back in 2007, this blog noted that AC Grayling’s distaste for oil had led him to produce a less than rational argument. “…what the cost of the Iraq war to date would have funded in the way of research into alternative energy sources?”, asked Grayling, channelling the contemporary narrative of the time that wars between men are ‘about oil’, the implication being that ‘alternative energy’ sources existed in equal or greater abundance than crude, but that somehow the substance itself turns men into mad addicts. A more easily observed phenomenon is that environmentalism makes very clever men say very stupid things.

In 2008, I reviewed The Ethics of Climate Change by James Garvey, who was at the time working our of Cardiff University — an institution that seems to have attempted to identify itself with climate policy. A collection of more favourable reviews can be read at Garvey’s blog. I found it to be a hollow contribution to philosophy — an attempt to make an argument for ‘equality’ in environmental terms, without ever really interrogating environmentalism. That is neither ‘ethics’ nor philosophy; it is just preaching. To a choir.

Garvey tells us, ‘the larger moral problems won’t really bite unless you know something about our prospects, the prospects for us as a species, in the face of climate change. Those predictions are not rosy’. But without the dark vision made plausible by science, Garvey would not be able to make a case for such crude moral calculations – goodies, baddies, tragedies, poverty, victims and culprits – all of which act to displace from the discussion, a political understanding of equality. So much of Garvey’s view of the world depends on the science providing the most hideous nightmare, from which there is no escape, that it’s hard not to wonder if, in spite of his claim that there is more to his argument, the science is the ‘whole of it’, and is little more than storytelling.

The moral philosopher that needs a total catastrophe as the foundation of his moral argument probably isn’t doing any philosophy at all. The catastrophe is a fig leaf. I bumped into Garvey at an event where Nigel Lawson was introducing his (then) new book. But Garvey didn’t want to talk, and walked off, muttering ‘I don’t talk about science’ — a strange reaction from a man who edits a blog called ‘Talking Philosophy‘, the sister project of The Philosophy Magazine.

A post on Talking Philosophy was linked to by Shub Niggurath on Twitter. The post is by Rupert Read, reader of philosophy at that infamous climate institution, UEA, and a Green Party activist who blogs at http://rupertsread.blogspot.co.uk/.

At Talking Philosophy, Read claims to explain ‘The real reason why libertarians become climate-deniers‘. This gives us another chance to see what — if anything — is going on in the philosophical ground of environmentalism. And its an undignified start…

We live at a point in history at which the demand for individual freedom has never been stronger — or more potentially dangerous. For this demand — the product of good things, such as the refusal to submit to arbitrary tyranny characteristic of ‘the Enlightenment’, and of bad things, such as the rise of consumerism at the expense of solidarity and sociability — threatens to make it impossible to organise a sane, collective democratic response to the immense challenges now facing us as peoples and as a species. ”How dare you interfere with my ‘right’ to burn coal / to drive / to fly; how dare you interfere with my business’s ‘right’ to pollute?” The form of such sentiments would have seemed plain bizarre, almost everywhere in the world, until a few centuries ago; and to uncaptive minds (and un-neo-liberalised societies) still does. …But it is a sentiment that can seem close to ‘common sense’ in more and more of the world: even though it threatens to cut off at the knees action to prevent existential threats to our collective survival, let alone our flourishing.

Straight from the horses mouth: contemporary society’s material expectations are bizarre — people living in the dark ages say so. This is followed by the familiar motif, ‘existential threats to our collective survival’ — the moral philosopher as blackmailer, again. The demand for individual freedom is dangerous, says read.

But is it true that ‘We live at a point in history at which the demand for individual freedom has never been stronger’? Read confuses ‘the demand for individual freedom’ as the availability of stuff — supermarkets and cheap clothes. We should note that in many countries characterised by very strict religious laws, one can nonetheless shop almost endlessly. And in spite of the abundance of shops here in the UK, other individual freedoms have been eroded. We’re freer to buy things, perhaps. But try lighting up a cigarette in a pub. We may be wealthier, but the state is arguably far more extended into the private realm than ever before, my favourite example of which is the ‘happiness agenda‘, in which the UK government began its attempt to take on responsibility for our emotional lives.

It is telling that Read conceives of shopping and liberty as equivalents. But rumours of ‘consumerism’ driving hoards of plebs unchecked through shopping centres have little foundation. The objection seems to be that poorer people can afford cheaper clothing and cheaper good quality food, not kept in their place by the necessities which trapped peasants and serfs in their condition. Read says the end of arbitrary tyranny is a good thing… but does he mean it?

Can he really mean it if, first, he thinks of liberty as libertarians conceive of it as meaning little more than consumer indulgence, and second, if he thinks abundance is the enemy of ‘solidarity and sociability’, as though austerity would unite the Nation once more? The question here that Read fails to reflect on is the possibility that his desire for what he calls ‘solidarity and sociability’ isn’t in fact a desire for order as only he prefers it — that he and his movement have been unable to put forward an argument for ‘solidarity and sociability’, and thus descend to blackmail in order to achieve the next best thing: obedience in lieu of assent. More charitably, Read, feeling alienated by contemporary society and its lack of meaning, experiences the material world in crisis. Either way, the impulse is narcissistic. And it is this failure to reflect on their own arguments that seems to characterise environmentalists’ attempts to set out their agenda.

Read continues,

Such alleged rights to complete (sic.) individual liberty are expressed most strongly by ‘libertarians’.

Liberty is not a straightforward concept. And so libertarianism is a broad category of thought, not all of which is formulated as libertarianism as such — people who identify as libertarians hail from left, right, and against politics. But the thing that libertarians would most likely emphasise in response to some incursion of this putative rights to enjoy consumer society is not the ‘right’ to consume, but the basis on which such an incursion was legitimised. If you say to me, “Don’t eat that burger”, my reply is not “it’s my right to eat it”, but “what’s it got to do with you?” The libertarian does not need a ‘right’ to eat a burger; he doesn’t think you have a right to prevent him.

It is perhaps a subtle difference. But the Moral philosopher seems to want to render in black and white what are actually nuanced ideas. And this creates a second, bigger problem for Read. As well as lacking insight into his own argument, he does not give a faithful account of the ideas he wants to scrutinise — a fatal failure for a philosopher.

Now, before I go any further (because you already know from my title that this article is going to be tough on libertarians), I should like to say for the record that some of my best friends (and some of those I most intellectually admire) are libertarians. Honestly: I mean it. Being of a libertarian cast of mind can be a sign of intellectual strength, of fibre; of a healthy iconoclasm. It can entail intellectual autonomy in its true sense. A libertarian of one kind or another can be a joy to be around.

But too often, far too often, ‘libertarianism’ nowadays involves a fantasy of atomism; and an unhealthy dogmatic contrarianism. Too often, ironically, it involves precisely the dreary conformism so wonderfully satirized at the key moment in The life of Brian, where the crowd repeats, altogether, like automata, the refrain “We are all individuals”. Too often, libertarians to a man (and, tellingly, virtually all rank-and-file libertarians are males) think that they are being radical and different: by all being exactly the same as each other. Dogmatic, boringly-contrarian hyper-‘individualists’ with a fixed set of beliefs impervious to rational discussion. Adherents of an ‘ism’, in the worst sense.

So which is it? Is it the preamble, which allows that some libertarians demonstrate the virtues of ‘intellectual strength, of fibre; of a healthy iconoclasm’? Or are libertarians, as the caveat proclaims, ‘to a man‘ deluded into thinking that they are ‘radical and different’ when they are all ‘exactly the same as each other. Dogmatic, boringly-contrarian hyper-‘individualists’ with a fixed set of beliefs impervious to rational discussion’? It cannot be both.

And what are these beliefs? Were they in fact so dogmatically-held, it would be easier to take issue with the beliefs than the act of believing them; Read turns liberarianism from an -ism into a character flaw. The moral philosopher takes a diversion into sociology…

Such ‘libertarianism’ is an ideology that seems to have found its moment, or at least its niche, in a consumerist economistic world that is fixated on the alleged specialness and uniqueness of the individual (albeit that, as already made plain, it is hard to square the notion that this is or could be libertarianism’s ‘moment’ with the most basic acquaintance with the social and ecological limits to growth as our societies are starting literally to encounter them). ‘Libertarianism’ is evergreen in the USA, but, bizarrely, became even more popular in the immediate wake of the financial crisis (A crisis caused, one might innocently have supposed, by too much license being granted to many powerless and powerful economic actors: in the latter category, most notably the banks and cognate dubious financial institutions…).

Here we see the problem of Read failing to interrogate his own perspective fully emerging. The ‘social and ecological limits to growth’ are not manifesting in reality. Indexmundi reports global GDP as follows

1999 3

2000 4.8

2001 2.7

2003 3.8

2004 4.9

2005 4.7

2006 5.3

2007 5.2

2008 3.1

2009 -0.7

2010 4.9

2011 3.7

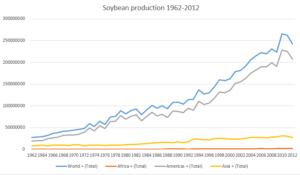

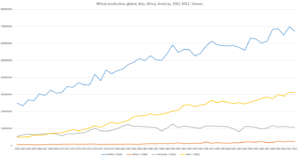

Only a few months in the last 20 years show negative growth. This has been discussed previously as ‘the environmentalists paradox‘. The world is richer, and its population living longer and healthier lives than ever before. The limits that Read asserts exist in the present do not exist in fact.

In order to agree with Read, we need to presuppose that limits have been encountered. But it is the tendency of environmentalists like Read to see problems that certainly do exist, such as poverty, as encounters with a limit. In this they make the mistake of naturalising problems, as though were the weather in some far off place slightly more stable, it would give more comfort to the poor. So much for the environmentalist’s emphasis on ‘solidarity and sociability’ — he only thinks he owes someone thousands of miles away a commitment not to make his weather slightly worse. And worse, he thinks that the problems experienced by poorer people are problems transmitted by the weather.

And Read continues to fail to reproduce the libertarian argument faithfully, wondering how it was that the ideology became more popular in the wake of the banking crisis and economic recession. “too much license” was “granted to many powerless and powerful economic actors: in the latter category, most notably the banks and cognate dubious financial institutions”, says Read scratching his head. But that was precisely the point made by libertarians.

Just as Read did not understand that the libertarian objection to the injunction “don’t eat that burger” was not his assertion to a right, but a questioning of the legitimacy of the injunction, Read misunderstands the libertarian’s distaste for the regulation of financial institutions. At issue is not the freedom of banks to do as they will such that, unconstrained, they cause some crisis or other. The libertarian objection was that the crisis was caused by government’s proximity to financial institutions. The loudest complaints about the bailouts came from libertarians, one of the most popular arguments being that governments and banks are in cahoots, made possible by fractional reserve banking — legal counterfitting, on the libertarian perspective — to do the bidding of rich and powerful people. No libertarian I am aware of argues that financial institutions should not be the subject of regulation and the law, but on the contrary that financial institutions should be subject to strict regulation, not merely regulation, changed according to the whims of the government.

Read cannot complain that the libertarian argument is hard to find. Here is the first Youtube video I found when searching with the terms “ron paul” and “banking crisis”…

… And he counted libertarians amongst his own friends, who are victims of some dogma. Yet he cannot even identify the dogma to reproduce it to criticise it. He insists that these libertarians are impervious to his reasoning with them, and yet he manifestly has not heard their argument.

But the more revealing thing is Read’s claim that the popularity of libertarianism is driven by the ideology of the moment, with its “alleged specialness and uniqueness of the individual”.

I argue precisely the opposite: that the prevalent mode of politics is not one which celebrates the “specialness and uniqueness of the individual”, but on the contrary, has taken aim at it. The evidence of this is not found in shopping malls and the High Street, but in the foundations of post-democratic political institutions like the European Union and the United Nations. If shopping is a distraction from the Good Life, people in shops are a bigger distraction for the moral or political philosopher. It is telling that Read looks for politics in the place you buy your shoes and supper, not in the organisations which in fact decide our futures. And on this point, Read says,

In the UK, it is a striking element in the rise to popularity of UKIP: for, while UKIP is socially-regressive/reactionary, it is very much a would-be libertarian party, the rich man’s friend, in terms of its economic ambitions: it is for a flat tax, for ‘free-trade’-deals the world over, for a bonfire of regulations, for the selling-off of our public services, and so on. (Incidentally, this makes the apparent rise in working-class (or indeed middle-class) support for UKIP at the present time an exemplary case of turkeys voting for Christmas. Someone who isn’t one of the richest 1% who votes UKIP is acting as a brilliant ally of their own gravediggers.)

Read brilliantly — albeit unwittingly — crystallises the phenomenon which in fact has driven UKIP’s ascendency: the arrogance of a political class (in which I include academics who have prostituted their positions to policy-relevant ‘research’) who proclaim that the public are better off with them, but who do not trust the public with the right to make the choice to vote against them. Leaving aside the claims about UKIP being socially regressive/reactionary (they’re not) and their flat tax (which isn’t their policy), Read thinks that anyone who voted for UKIP, but who isn’t rich, is stupid. Indeed, the European Union thinks people are stupid. It thinks people are too stupid to appoint national governments through the ballot box. The vote for UKIP was a vote against the accretion of power away from democratic institutions, and all that goes with it. The possibility that people may have judged that, for the time being, seemingly progressive labour rights might be worth foregoing for the sake of a greater degree of political autonomy has not occurred to Read. He doesn’t credit people with the sense to make that decision.

Last week, similar comments to Read’s were made in The Conversation. ‘Right-wing flames that have licked Europe’, claimed Professor of Psychology at Trinity College Dublin, Ian H Robertson, were ‘fanned by lack of education’.

Need for closure tends to produce what is known as “essentialist thinking” – which means creating simple categories – for example “blacks” – members of whom automatically have characteristics associated with the category. This easy and quick thinking habit avoids the need for any more complex analysis of individuals: if high NFC people are faced with contrary evidence to their quick categorization – eg a member of the out-group who is better educated than they are – they experience this as very uncomfortable and tend to shy away from it.

High NFC individuals are also very attracted to authoritarian ideologies because such ideologies satisfy their deepest psychological needs for certainty, quick solutions and unchanging, permanent answers.

[…]

Education builds IQ and IQ reduces prejudice – though obviously not on the part of some bright but ruthless far right party leaders. Educational also helps people think more abstractly, and if you get someone to think about a problem in more abstract terms, their prejudice towards the out-group is temporarily diminished.

Heav’n save us from ideologues bearing simple categories and their psychological need for certainty! That the idea of such an instrumental use of education can be uttered without blushes might indicate that the individual isn’t quite the first order of politics. People are stupid — they must be educated.

So not only does Read not even understand his own argument — much less advance it coherently — and not only does he fail to reproduce the argument of stupid people labouring under some dogma, he, like Robertson doesn’t even understand the context of the apparent debate between him and them.

Read continues…

This article concerns a contradiction at the heart of the contemporary strangely-widespread ‘ism’ that is libertarianism. A contradiction that, once it is understood, essentially destroys whatever apparent attractions it may have. And, surprisingly, shows libertarianism now to be a closer ally to cod-‘Post-Modernism’ or to the most problematic elements of ‘New Age’ thinking than to that of the Enlightenment…

It’s a big claim. But the reality is somewhat underwhelming. Libertarians like to emphasise their commitment to truthfulness and objectivity, observes Read. But a commitment to truth is a constraint on the individual, whose freedom is paramount.

I don’t think I have yet met a libertarian who has asserted the right to believe that the moon is made of cheese in spite of his knowledge that it is mainly rock (with a little bit of cheese). Certainly, I have met libertarians of a more Randian bent, who lay it on a bit thick sometimes. But Read is just as guilty here, as any adherent of any ideology of laying it on thick.

Note the conspicuous absence in Read’s argument of what Truth has been denied. He says the libertarian denies ‘limits to growth’, but the argument is about ‘denial’ of climate change. And there is good historic and scientific evidence that the limits to growth thesis has been wrong since its inception, as evidenced in no small part by the continued existence of England, which Ehrlich predicted would have been destroyed by now.

This lack of precision in Read’s argument is a case of what I call a a consensus without an object. Although a libertarian might well agree that CO2 absorbs/scatters IR radiation, and that this will produce a warming effect, and agree that this effect could cause problems, and could even agree that it requires the intervention of some agency, he doesn’t have to agree with Read that this represents either a global catastrophe in the making, or a palpable ‘limit to growth’. Read gets to claim as the consensus position whatever suits his argument, without attention to the actual substance of the consensus, or its putative denial. He uses climate change and ‘limits to growth’ interchangeably.

This cannot be over-stated. The actual consensus on climate change is largely inconsequential, and does not yet include either the claim that any significant Nth-order detrimental effect of climate change has been detected, or that any projected consequence can only be addressed through mitigation, rather than through measures that I wouldn’t even call ‘adaptation’. Most future and extant problems that are attributed to climate change are problems that would not exist in a wealthy (or wealthier) economy. But growth, says Read, is impossible, it has reached its physical limit. And in this move he reveals that the apparent scientific conclusion of the ‘limits to growth’ thesis is in fact the premise of its political argument. Read takes it for granted. That does not make the prognostications that Read takes at face value wrong, but it does raise a question mark over what he claims as unimpeachable truth. One can make the point that somebody standing at the edge of the sea at low tide faces death if he does not move. But he has legs and can walk, and likely has the will to survive. The projection is correct, scientifically sound, True. But it is not the whole story, and worse, takes competing accounts of what is going on, and what could happen off the table, to force us into a course of action.

This explains the extraordinary and pitiful sight of so many libertarians finding themselves attracted to climate-denial and similarly pathetic evasions of the absolute ‘constraint’ that truth and rationality force upon anyone and everyone who is prepared to face the truth, at the present time. Such denial is over-determined. Libertarians have various strong motivations for not wanting to believe in the ecological limits to growth: such limits often recommend state-action / undermine the profitability of some out-of-date businesses (e.g. coal and fracking companies) that fund some libertarian-leaning thinktank-work. Limits undermine the case for deregulation. The limits to growth evince a powerful case in point of the need for a fundamentally precautious outlook: anathema to the reckless Promethean fantasies that animate much libertarianism. Furthermore: Libertarianism depends for its credibility on our being able to determine what individuals’ rights are, and to separate out individuals completely from one another. Our massive inter-dependence as social animals in a world of ecology (even more so, actually, in an internationalised and networked world, of course) undermines this, by making for example our responsibility for pollution a profoundly complex matter of inter-dependence that flies in the face of silly notions of being able to have property-rights in everything (Are we supposed to be able to buy and sell quotas in cigarette-smoke?: Much easier to deny that passive smoking causes cancer.). Above all though: libertarians can’t stand to be told that they don’t have as much epistemic right as anyone else on any topic that they like to think they understand or have some ‘rights’ in relation to: “Who are you to tell me that I have to defer to some scientist?”

Read does not know his own movement’s history very well. It was Garret Hardin who suggested that private property could solve the problem of environmental destruction. In the tragedy of the commons, Hardin argued that privatising common land was the best measure against over-exploitation by ‘free-riders’. Hardin’s theory is the ground for cap-and-trade and similar systems. So in this important respect, Read imagines a philosophical left-right divide between libertarians and environmentalists that simply does not exist (though may exist in others). In fact, it is therefore remarkable, in these green times, that more libertarians haven’t attempted to use the environment to advance their views.

On Read’s view, the libertarian imagines that he has a ‘right’ to his own scientific knowledge just as I have a ‘right’ to a burger, which is trampled on by scientist, whose science otherwise demands deference. This is his ‘gotcha’. But it is weak, in part because Read again fails to reproduce the libertarian’s argument, but more problematically this time, forgets to check his own position. The libertarian’s apparent denial forgets the proposition which has been rejected: Read’s claim that there exist ‘limits to growth’.

In other words, on the libertarian point of view, Read over-states the interdependence of people with the planet’s natural processes. And this is the real reason libertarians seem to ‘deny’ climate change (though they mostly don’t).

Recall that the environmentalist moral philosopher holds the public in low esteem. Compare this with the libertarian’s estimation of the far more robust individual. As I have pointed out previously, the low estimation of the ordinary human is coincident with an emphasis on the environment, and the rejection of both happens for good reasons. For instance, Chris Mooney proposed a while back, that there may be a biological basis for political preference, which, in the main, forced those of a more conservative persuasion to reject science. They were blinded by ideology, he said. I replied,

The short answer to Mooney here is that, if the putative Liberal/Left appears to be less-’ideologically-driven’ than the Right, it is because it is that much more hollow. This is not a defence of conservatism (I am not a conservative), it’s merely a fact that we can see the disintegration of the Left in general over the course of the C20th. It has sought legitimacy for its ideas not amongst the public, but in the scientific academy. Meanwhile, it seems obvious enough that a more coherent ‘ideology’, and concomitant views on social organisation might mediate the impact of seemingly self-evident ‘facts’. That is to say that a conservative might just be less terrified by climate change than a ‘liberal’ because the conservative puts more emphasis on wealth. The liberal/Left, however, has emphasised wealth less and less as it conceded to capitalism.

In other words, Mooney’s conservative and Read’s libertarian seem to have a better understanding that humans create wealth. (And for that matter, so too did many Marxists). On the limits to growth perspective, humans merely take wealth from nature. What Read describes as ‘interdependence’ between ourselves and with the natural world, isn’t as much a departure from the limits of consumerism, but their fullest possible expression: we are just consumers, not producers or creators. Moreover, rather than putting us into a more healthy relationship with each other (and the natural world) than is permitted in consumer society (to the extent that it exists), Read conceives of relationships as merely metabolic. Read wants to take you out of the consumer-capitalist machine, and make you a mere component of Spaceship Earth, which only he gets to drive.

In other words, in order to believe what Read says, you have to presuppose that there are limits to growth, and that they have been identified, and are a scientific fact. But they have not been identified, and they are not a fact. Worse, they are not really a claim about the material world at all, but of the limitations of humans. It follows that, if you think people are stupid, and that wealth comes from a delicate balance of natural processes which are easily disturbed by stupid people, you will lean towards the green perspective. If, conversely, you think that humans are capable of navigating the world, and improving its and themselves, without the authority of experts and their proxies, you are more likely to take a sceptical view of environmentalism. This is the point of difference in debates about the environment, especially climate change.

But read disagrees:

This then reaches the nub of the issue, and explains the truly-tragic spectacle of someone like Jamie Whyte — a critical thinking guru who made his name as a hardline advocate of truth, objectivity and rationality arguing (quite rightly, and against the current of our time, insofar as that current is consumeristic, individualistic, and (therefore) relativistic/subjectivistic) that no-one has an automatic right to their own opinion (You have to earn that right, through knowledge or evidence or good reasoning or the like) — becoming a climate-denier. His libertarian love for truth and reason has finally careened — crashed — right into and up against a limit: his libertarian love for (big business / the unfettered pursuit of Mammon and, more important still) having the right to — the freedom to — his own opinion, no matter what. A lover of truth and reason, driven to deny the most crucial truth about the world today (that pollution is on the verge of collapsing our civilisation); his subjectivising of everything important turning finally to destroying his love for truth itself. . . Truly a tragic spectacle. Or perhaps we should say: truly farcical.

Read’s conflation of ‘relativistic’ and ‘subjectivistic’ is interesting. Postmodern philosophy has been associated with relativism, especially in ethics. But largely at the expense of subjectivity. Relativism seems to deny that truth can be located. But science proceeds by eliminating, rather than denying subjective effects. You can’t do science without subjectivity. Put simply, differences between subjective experiences can be reconciled, whereas relativistic effects are seemingly insurmountable. As this account of postmodern philosopher Lyotard explains,

Like many other prominent French thinkers of his generation (such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and Gilles Deleuze), Lyotard develops critiques of the subject and of humanism. Lyotard’s misgivings about the subject as a central epistemological category can be understood in terms of his concern for difference, multiplicity, and the limits of organisational systems. For Lyotard the subject as traditionally understood in philosophy acts as a central point for the organisation of knowledge, eliminating difference and disorderly elements. Lyotard seeks to dethrone the subject from this organisational role, which in effect means decentring it as a philosophical category. He sees the subject not as primary, foundational, and central, but as one element among others which should be examined by thought. Furthermore, he does not see the subject as a transcendent and immutable entity, but as produced by wider social and political forces.

[…]

He calls into question the powers of reason, asserts the importance of nonrational forces such as sensations and emotions, rejects humanism and the traditional philosophical notion of the human being as the central subject of knowledge, champions heterogeneity and difference, and suggests that the understanding of society in terms of “progress” has been made obsolete by the scientific, technological, political and cultural changes of the late twentieth century.

Accordingly, on many contemporary pseudo-scientific and scientistic rants in the postmodern era, subjective experience is merely an illusion (e.g. Dawkins, Dennet, Blackmore) — a difficult problem with the question ‘who the **** do you think you are?’, kicked into the long grass — reflecting the genetic determinism of Mooney, and the nasty near-eugenics of Robertson. And of course, Read. The belittling of individuals and their faculties… subjects… is very much a postmodern phenomenon, in which the belittlers grasp for authority. So the really remarkable irony is that Read continues:

The remarkable irony here is that libertarianism, allegedly congenitally against ‘political correctness’ and other post-modern fads, allegedly a staunch defender of the Enlightenment against the forces of unreason, has itself become the most ‘Post-Modern’ of doctrines. A new, extreme form of individualised relativism; an unthinking product of (the worst element of) its/our time (insofar as this is a time of ‘self-realization’, and ultimately of license). Libertarianism, including the perverse and deadly denial of ecological constraints, is, far from being a crusty enemy of the ‘New Age’, in this sense the ultimate bastard child of the 1960s.

“Postmodern” has become a pejorative used to diminish critics of ‘science’. But Lyotard in fact anticipates much about the climate debate. The postmodern condition, explained Lytoard, is ‘incredulity towards meta-narratives’, noting the displacement of religion, Marxism, and other encompassing ‘narratives’ in capitalist economies by science — ‘information’ had become the principal commodity. Metanararatives are, after all, what drives the thinking subject.

Isn’t this what we see in Read, and, in the previous posts, Paul Nurse, eschewing ‘ideology and politics’, in favour of ‘science’, concerned about all the little people, vulnerable to ideologues? And ditto Read, who sees no more in subjectivity than the slavish impulse to go shopping, driven by the consumerist ideology of our time, ignorant of the reality which looms over it. On Read’s view, we’re all ‘unthinking products’ in search of product. And don’t we see in Nurse and Read desperate arguments about whose information is the most legitimate, and should thus drive policy-making (pka, politics)?

But none of this is as remarkable an irony as Read’s closing words…

It takes strength, fibre, it takes a truly philosophical sensibility — it takes a willingness to understand that intellectual autonomy in its true sense essentially requires submission to reality — to be able to acknowledge the truth; rather than to deny it.

The real object of Read’s ire is disobedience. Notice that, in his rant, he does not produce a single instance of ‘the reality of climate change’ being denied at all, let alone in the words of a single libertarian, much less all of libertarianism, in all its forms. We have to take it for granted that the object of the denial is true, and that the deniers denied the object. Not once does he let libertarianism speak for itself… Not even a quotation mark litters his argument that climate-change denying libertarians cannot think for themselves. It is not obedience to reality that Read is demanding, but obedience to scientific authority — science as an institution, not science as a process through which ‘reality’ — the material world — can begin to be understood. God forbid that the un-anointed should be allowed to use the scientific method for themselves.

There is no ‘philosophical sensibility’ about Read’s argument. If there were, we would see an actual dialogue between Read and libertarianism, on the subject of climate change and limits to growth. The ‘reality’, or ‘truth’ to which he demands we submit is not scientific fact, but a presupposition of political ecology, that there exist ‘limits’. Note furthermore, that these limits are not equivalent to ‘climate change is happening’, but a far-off consequence of climate change, if it is happening, and even then, only if we take the remaining precepts of environmentalism for granted.

We see this often in the climate debate: many figures, from Cook and his 97%, through to John Gummer restyled as Lord Deben, pronouncing on ‘deniers’ and what they deny, without ever actually taking any notice of what was being ‘denied’ — the consensus without an object. And we see it so often that I think we can now call this other-isation of ‘deniers’ an essential characteristic of contemporary environmentalism’s argument:

* The ‘deniers’ are never identified.

* No account of the deniers’ arguments is ever given.

* The object of the deniers’ denial is never explained.

It’s like a debate, but without an interlocutor. Socrates in solitary confinement. A dialectic with no antithesis. And from that, we can establish:

* Environmentalism needs denial to exist.

* The deniers do not exist.

* The deniers are simply figments of environmentalists’ ideology or imagination.

* Environmentalists pick fights with phantom deniers to avoid actual debate.

If it doesn’t matter what the arguments are — be they scientific or ‘ideological’, right or wrong… If there is no dialogue, then there is no philosophising about what denialism is. There is only some kind of academic onanism. Meanwhile, a lot has been revealed about environmentalism, and the state of academic philosophy.

Read does not want assent to scientific fact. An entire legion of morons could give their assent to Read’s claim, to qualify as having ‘truly philosophical sensibility’ without him chucking them out of the philosophers’ circle jerk for not, in fact, having the gift of ‘intellectual autonomy in its true sense’. Anyone can assent to ‘reality’ without actually thinking about it. Read wants obedience.

Conclusion

People who want obedience hate liberty. It’s that simple. They see people acting on their own thoughts as a symptom of society breaking down, not a society made up of individuals cooperating and negotiating with each other autonomously, who have rejected the moral philosopher’s bogus imperative for good reasons. And in the case of environmentalists like Read, that sense of breakdown emerges in his views on the environment. It’s an infantile reaction to a world that does not conform to his wishes. Finding the reality hard to accept, he cannot tell the difference between the end of the world and his failure to assert himself over others. And there’s nothing that people with a sense of entitlement hate more than being challenged.

Angry, condescending academics are nothing new. And ridding the world of them would not make it a better place. But the Academy had a culture — was a culture — in which pig-ignorant angry, condescending academics could be kept in check, either by squabbles with each other, or through institutions like peer-review or through criticism from more reasonable academics. Either as cause or effect, academe seems no longer able to foster debate, especially on the issue of climate change. I suggest that one reason for this is the extension of University departments into governance. That’s not to say that academia has nothing to say about the organisation and functioning of government and society, but that there must be some principle, not unlike the separation of powers, which, once abandoned, turns those who can speak truth to power or hold it to account, merely become its instruments.

As we have seen with other UK academics and their departments — Lewandowsky and Cardiff University psychologists have been discussed here at length — the academic has turned his sights at the public in general and climate sceptics in particular. We have seen, in other words, mediocre academics make big names for themselves — ‘impact’ — by objectifying or pathologising impediments to official agendas, using the resources of the academy. Just as Lewandowsky couldn’t take the perspectives of climate sceptics in good faith — he had to probe inside their minds, using a shoddy internet survey — Read does not take issue with the arguments actually offered by actual climate change-denying libertarians, he takes issue with his own fantasy libertarian, abandoning all the rigour and practice that the discipline he belongs to has established over the course of millennia, to score cheap rhetorical points.

In a number of cases, there seems to be good evidence that the academy’s involvement with environmentalism seems to show that it has become dominated by contempt for the public, and hostility to interlocutors, even those within the academy. Like some kind of anti-proletarian Cultural Revolution, counter-revolutionaries are denounced, and orthodoxies — like Read’s weird limits-to-growth anti-capitalism — established. To anticipate Lewandowsky-esque criticism that this is conspiracy ‘ideation’, the point here is to say if only there were a green Mao, with a Little Green Book… There would then be some discipline to the green campaigning in academia, which could, in turn be engaged with, or even better, engage with its critics. But instead of environmentalism as a political philosophy or ‘ideology’ as such, we seem to see environmentalism as a phenomenon in which putative experts in fact eschew such discipline as it applies to them. This gives the lie to the Philosopher Kings. The Likes of Read, Lewandowsky and all those Consensus Police don’t seem to elevate the academy as an institution which is as good for wider society as much as they seem to think that academics are entitled to rule. They have convinced themselves utterly that without them, the world will surely fall apart. But their emotional sensitivity to criticism suggests that such a view is not grounded in fact, and that what is at stake is their own tenuous hold. Like a paranoid tyrant — like Stalin, perhaps — nervous political power lashes out at the threats it perceives, real or not.

Here is Read’s explanation for his failure to win a seat at the recent European elections, and his party’s failure to increase their share of the vote.

I blame the tiny handful of multi-millionaires who bankroll the Party that shall remain nameless, and the national media for giving them bucketloads of coverage while ignoring the rise of the Green Party in the opinion polls during the campaign. I hope that once people realise what the Party that shall remain nameless actually stands for they will turn away from it in disgust, and turn to the Green Party, which offers a positive alternative to the old, failed parties.

It looks like Read wants to blame millionaires — Boo! Hiss! Millionaires!. But look deeper at the logic of the argument, and what it in fact says is that the voting public are stupid, and have been hoodwinked. This contempt is central to environmentalism, which explains why it suffers, even when it condescends to testing itself through democratic processes. And it explains why environmentalism is inclined to catastrophism. And that explains why environmentalists hate liberty. ‘Reality’ has nothing to do with it. The cause is misanthropic narcissism.

BBC Science Broadcasters — Bubble, BS, or Cabal?

The previous post here generated a bit of Twitter twitchiness from one of the contributors to Horizon’s 50th anniversary celebration — Professor of Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham and TV presenter, Alice Roberts. A somewhat partial account of the exchanges was compiled on Storify by a Twitter troll, and can be seen here. Roberts was upset that my post had accused the Royal Society and the producers of Horizon of a conspiracy, and having an ‘agenda’.

This kind of passive-aggressive argumentation is another of the frustrating things, which is not unique to the climate debate, but finds particular expression in it. I criticised two public institutions, but the criticism is taken personally by one of their members. Twitter is not a nuanced medium, so the discussion — such as it was — descended into the wrongs of accusing people of having an ‘agenda’. I did not quite realise that Roberts had such a problem with the word ‘agenda’, which she had introduced, until too late. I tried to explain that it isn’t a helpful word, that it was her word, and that it doesn’t really explain what I was saying in the article. So here is another attempt, for Roberts’ benefit.

In fact, I hadn’t really criticised Roberts. She had pointed out that, ‘It’s fascinating to look at Horizon over its five decades, and to see how the tone of the series changed, reflecting shifting attitudes towards science and technology’. I agreed, ‘Roberts makes an interesting point, and one that is made here. The optimism and technological progress of the sixties gave way to a deep pessimism about the future. And it was between these two decades that environmentalism was born.’ But I didn’t think it was interesting enough just to note that the tone of Horizon has changed, reflecting shifting attitudes as though they were just a spontaneous transformation of no more than consumer (i.e. viewer) tastes. There is much more reflected in this transformation that Roberts seems willing to admit, and there are a great deal of ‘whys’ that should help to explain it.

For instance, one of my favourite historical moments with which I like to compare contemporary thinking on science and its role in society is Kennedy’s ‘Moon Landing’ speeches. Today’s ‘moon landing’ is said to be the issue of climate change…

The science of climate change is the moon landing of our day. This is idealism in a technical language. The scientists and the idealists will, once again, be the same people. The discoveries in the laboratory will be matters of life and death. Nothing could be more vital, nothing could be more exciting. Tony Blair, November, 2006.

That to me is the starkest demonstration of the change in society’s relationship with science: from the technological optimism of the post war era, through the pessimism of the 1970s, and on to the narcissism of the early 21st century. It says something that the moon landing is the bench mark — the thing that world leaders struggling for a legacy strive for, rather than exceed. So Blair (though he was not alone) is forced to create a pastiche of Kennedy. “Look, this is my Moon-Landing speech”, he tells us. He can reinvent the moment, unite the nation, Be the One.

This is not to put Kennedy on a pedestal. There is no doubting that, as much as Kennedy emphasised scientific and technological progress, the moon mission was, from its inception, deeply political, if for no other reason than the fact that it was rooted in perhaps the deepest geopolitical and ideological divide in history. Had Blair been a politician in 1960s USA, rather than in late 1990s UK, he would not have had to try so hard (and fail) to reinvent the circumstances that Kennedy faced — climate change as moon landing and the War on Terror as the Cold War. And we can only guess at what Kennedy might have done if he only had men in caves and foreign strains of influenza to deal with — it would naive to believe that the project to put a man on the moon was, As Kennedy claimed, channelling George Mallory, ‘because it was there’. The end in sight was not just human footprints on the moon for the sake of it, but variously concerned with global and domestic political and strategic matters, not least of which was a grand projet for the sake of an administration. But it was a giant leap, nonetheless. Blair continued setting out his far more modest leaps:

The Government’s Foresight programme which sets an agenda for future action on science is working out new strategies in flood and coastal defence, exploiting the electromagnetic spectrum; in cyber-trust and crime prevention, in addiction and drugs, the detection and identification of infectious disease, tackling obesity, sustainable management of energy and mental well-being.

The way in which politicians pitch and hitch themselves to science reveals much about the politics and ‘ideology’ of the era. (NB, I do not use ‘politics’ and ‘ideology’ interchangeably.) Kennedy’s aim for the moon and Blair’s emphasis in microbes, addicts, fat people, happiness and sustainability can’t be taken at face value. No doubt those priorities became those leaders’ policies, which is to say became items on their ‘agenda’. But there is a deeper meaning of the word ‘ideology’, which isn’t captured by either ‘politics’ or ‘agenda’. Why was Blair concerned with overweight and unhappy people, germs and sustainability where Kenendy was concerned with the lunar landing? It isn’t as simple as simply detecting that people are getting fatter and sadder, or that some virus or other is on the march, and it’s not enough to say that politicians respond to matters arising from without, alerted by researchers.

For example, the putative rise in obesity, in eras where poverty and its diseases were far more prevalent, would have been seen as a Good Thing. Food, glorious food… Even if we take it at face value that “rates of obesity are rising”, as it is often claimed, it is not axiomatically something that ought to concern the government of the day, but might be the responsibility of the owners of the mouths that food is being shoved into. What business of the state’s is our ‘mental well being’, really? In order to make our internal lives, and relative abundance — rather than scarcity — an issue for government, a broader shift in the relationship between the state and individuals needs to occur. Ditto other problems of affluent industrial society that seem to present challenges to government — mass transit and infectious diseases, climate change, and cyber-crime — seem to make the political establishment as hostile to development and economic growth as it is to the distinction between the public and private.

There was no ‘agenda’ as such that intends to alter the balance of responsibilities between individuals and government. But that was in the thinking of the UK government and the direction of its policies nonetheless. And it is not enough to say simply that scientists, with no particular attachment to ‘the agenda’ merely observe and report things like an increase in obesity, or potential threats like infectious disease and climate change. Scientists are not simply highlighting new outbreaks of flu, climate change, expanding waistlines and unhappiness, and the rest, because ‘they are there’. They have likely always been there. And more importantly, there is an extent to which things are found when they are sought. If not sad, fat, potential victims of bird flu, then some other issue would be there, playing the same role.

The ground on which the discussion with Roberts stands is not a landscape with a clearly delineated ‘science’ at one end and ‘politics and ideology’ at the other, as Paul Nurse desired. There are no straight lines here.

Kennedy’s ambition stands in contrast to Blair’s much lower horizons. Giving the former speech the benefit of the doubt, it aimed to expand the possibilities of humanity — a ‘giant leap for mankind’. Blair’s speech promised to protect us from ourselves — even including our emotional selves. This reflects Blair’s communitarian politics and ‘ideology’. There was no ideological battle for him, in which ideas about humanity were contested publicly and globally; those battles were over, and now people merely needed to be managed — saved from themselves, and from things that ordinary people cannot see. This is the transformation that is, with sufficient perspective, visible in politics and its relationship with science, but which is invisible to scientists, generally. That ideological shift is one in which ‘risk’ has become a central concept, where there were once contests about which principles society should organise itself around. That is not to hark back to some golden age of democracy, but to point out that a change has occurred, right or wrong, and to suggest that it should be interrogated.

This is not some fanciful, climate-denier-politico-waffle. Take it straight from the horse’s mouth:

Policy-making is usually about risk management.Thus, the handling of uncertainty in science is central to its support of sound policy-making.

In Uncertainty in science and its role in climate policy, Lenny Smith and the Blair Government’s climate economist, Nicholas Stern attempt to give this form of politics some justification in the face of questions about ‘uncertainty’. The precautionary principle allows risks — which could be zero or merely theoretical risks — to dominate political decision-making. Say Stern and Smith:

Scientific speculation, which is often deprecated within science, can be of value to the policy-maker as long as it is clearly labelled as speculation. Given that we cannot deduce a clear scientific view of what a 5◦C warmer world would look like, for example, speculation on what such a world might look like is of value if only because the policy-maker may erroneously conclude that adapting to the impacts of 5◦C would be straightforward. Science can be certain that the impacts would be huge even when it cannot quantify those impacts. Communicating this fact by describing what those impacts might be can be of value to the policy-maker. Thus, for the scientist supporting policy-making, the immediate aim may not be to reduce uncertainty, but first to better quantify, classify and communicate both the uncertainty and the potential outcomes in the context of policy-making. The immediate decision for policy-makers is whether the risks suggest a strong advantage in immediate action given what is known now.

Notice also, that the business of politics, is now called ‘policy-making’, and is “informed” by scientists, speculating. We all know the truth of what Stern and Smith say. When scientists speculate — and they often speculate wildly — it does not come ‘clearly labelled’ as speculation. It gets presented as fact. Notice, furthermore, that Smith and Stern do not chose, say, a 1 or 2 degree rise in temperature, but a whopping 5 degrees. Worst still is that after speculating that 5 degrees is plausible, scientists are invited to speculate about the effects of 5 degrees. And then on the effects of the effects of 5 degrees. A cascade of speculation emerges — an unleashing of the environmental imagination — in which the ‘ideology’ of environmentalism is unleashed: neither an ‘agenda’ as such, nor as coherent programme of ideas, but all of the unstated presuppositions, prejudices and mythology of green thought, made flesh in a science fiction story.

One does not have to look far for evidence of this in effect. In the latest Horizon episode, discussed in the previous post, the premise of malthusianism was evident through three of the stories presented in the episode: there are too many of us, we fly too much, we are running out of space to grow food, we are running out of water. They were presented as facts. But they were speculation, from a seemingly empirical basis, perhaps, but through green ideology. There may well be a growing population, but it is only a problem on the view in which is informed by environmentalism’s presuppositions. The idea that more people might be better at feeding themselves is anathema to population environmentalism, but yet there is good evidence that they are, and good arguments that they will continue to be, but which is evidence that it flatly ignored or sidelined by certain proponents of the environmental ‘message’. That message says that people are, in themselves, net risks.

The risk of things like avian flu, and fast food — as well as, now, running out of water, food and fuel and people in themselves — are the basis on which political power is now legitimised. Politicians now seek to identify risks where they once sought a mandate. And scientists are recruited into that project, just as NASA’s scientists were tasked with understanding how to send men into space.

In other words, science, as much as it is a technical means to a human ends in our hands, is equally a means to an ends in politicians hands. And that being the case, we can see in stories about how science has changed, broader social, political and ideological shifts.

Back to Roberts’s complaint, then, that I had unfairly accused the BBC and the Royal Society of having an ‘agenda’:

Prof Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

@clim8resistance @omnologos You write as though you think that the Royal Soc, the BBC & Horizon producers have a secret agenda. They don’t.Prof Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

@clim8resistance @omnologos At least, I think I would have discovered it by now if they did (unless I’m really thick)Prof Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

.@clim8resistance @omnologos It’s not an agenda- this is the principle at work here. Question everything. Look for evidence. Share knowledgeProf Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

@clim8resistance @omnologos Oh yes! It’s a conspiracy. All of us academics who freelance for the BBC are in on it. (NOT)Prof Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

@clim8resistance @omnologos Amazing! Who’s setting this agenda? Aliens?Prof Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

@clim8resistance @omnologos Fantastic. We’re hoodwinking the ‘public’, somehow, and don’t know we’re doing it. Who’s being patronising?Prof Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

@omnologos @clim8resistance then suggesting they’re too stupid to realise that they have an agenda… that’s a conspiracy too far.Prof Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

@omnologos @clim8resistance None of my interactions with the RS and Horizon producers have made me think there’s any agenda beyond that…Prof Alice Roberts @DrAliceRoberts

@omnologos @clim8resistance (I hate doing this) of setting up a dialogue between scientists and the wider public.

I think it has been shown here that taking science — especially where it has, on Nurse’s view ‘implications for policy’ — at face value is a terrible mistake. The epitome of the error is in the Malthusianism of Paul Ehrlich, which Horizon first gave a favourable treatment of in the 1970s, and has not done anything (as far as I can tell) in the meanwhile to do anything to rebut, in spite of its total failure (or at the least, the controversy that surrounds it), and its undoubted influence over global and domestic political institutions. And the same thinking is reproduced in the latest episode of Horizon. The Royal Society and its presidents, who Roberts claim have no agenda, made him a fellow. And, seeking the political power that his dire predictions seem to generate, launched a study that proceeded from his work on population. Here is Sir John Sulston FRS, Chair of the Institute for Science, Ethics & Innovation, University of Manchester, discussing the Royal Society’s findings.

Roberts wants to claim that the Royal Society has no agenda. But Sulston has just presented a political manifesto, in which he instructs the world that it must abandon the principles on which productive life is organised — trade, on his view. It is as radical and far-reaching as any capitalist or communist manifesto. But rather than privileging institutions like private property or an economic class such as the proletariat, this manifesto puts scientific bureaucracies at the top table.

Politics is, on one definition, ‘Who gets what, when, and how” (Harold Lasswell). And Sulston has just pronounced on the rights and wrongs of who gets what, when and how. He has made prescriptive statements about how society ought to be organised, and who should be entitled to what, based on claims about how he (and the RS) thinks the world is. For the sense he makes, he might just as well have announced that it is flat.

It is obvious, then, that the Royal Society does have an agenda of some kind. It isn’t just looking at things under microscopes; it wants to effect political change in the world, and it wants to be an influential agent in that change. Unfortunately, however, the Royal Society — and I assume, Roberts — does not recognise that this is a political agenda. It thinks it is science.

But not all things that proceed from an empirical basis are science. As discussed above, how we move through and synthesise statistics about society’s relationship with the planet is sensitive to prejudices and presuppositions — ideology. And the problem with ideology is, unlike ‘agendas’ and ‘politics’, that it is often invisible. To the likes of Roberts and the FRSs, it may seem that Sulston’s manifesto is as self-evident as 2+2… But to me at least, he is manifestly not speaking about things that can be understood as material phenomena — objects of science. He presupposes things about people as individuals and in numbers, and their interactions with the natural world, to overstate our dependence on it. He eschews the insight that can be found in political thinking from Smith, through Marx, and onwards, contra Malthus, that it is people who depend on themselves, in spite of nature and her whims. The loaf of bread at my supermarket owes no more to natural processes than does the computer on my desktop. As Matt Ridley observes in The Rational Optimist, it is people, cooperating, which makes this life possible, not Nature’s Providence.

So let us clear a few things up for Roberts.

The ‘agenda’ is not secret, but it is not explicit. The Royal Society and its members do not recognise that their own positions are ideological, or political. That is not to call them ‘stupid’, but to say that science is not always sufficient to recognise its researchers’ presuppositions as political, in order to exclude them.

It is not a ‘conspiracy’. The ‘agenda’ is not to manoeuvre itself into political power subversively ot covertly. But this doesn’t exclude the possibility that the Royal Society and its kin are seeking greater power for themselves, either in good faith, as a commitment to the idea that institutional science should play a bigger role in society, or in bad faith — I don’t care to speculate.

This can be explained simply: a bad idea can be advanced in good faith. Ditto, seemingly good ideas can be advanced in bad faith.

Roberts asks us to believe that the ‘agenda’ is no more than “Question everything. Look for evidence. Share knowledge.” and “setting up a dialogue between scientists and the wider public”. She is naive. And I count such self-deception as bad faith: Roberts didn’t like being questioned, didn’t like the evidence being interrogated, and she didn’t like the knowledge she didn’t like being shared. And she certainly didn’t like the dialogue with the public she was, for a moment at least, engaged with. Paul Nurse, similarly, didn’t like science being questioned, so he made a TV show about it. Science is not for questioning. It is for our humble respect. Just as TV broadcasting has become mere collection of awesome visual phenomena, so we are told to defer to science as though it had just produced some miracle, the awe demanding our obedience.

Which brings us to the BBC and Horizon.

I don’t see a great gulf between the Royal Society and the BBC. That is to say, I don’t see much of a difference between the broadcasting establishment and the scientific establishment, much less at their nexus. Certainly, the BBC do not seem to have gone out of their way to challenge the authority of the Royal Society, much less its claims — highly contestable claims in many cases. Yet any institution that so many journalists call their home should have been able to find something to say about it. Even George Monbiot managed to call them ‘idiot savants’ for their backing of GM crop production. But this should not surprise us. There is no culture at the BBC of challenging authority in any meaningful way. Its job, from its creation, was to extol the virtues of the British Establishment, and to transmit them across the planet.

The BBC is a bubble. Its broadcasting departments are bubbles. The scientific establishment is a bubble. Perspectives from without the bubble are met with ire much like Roberts’s and Nurses: challenges to the authority and the claims of the establishment are met with derision, the critics belittled as “anti-science”. Like the phenomenon of environmental journalism, the BBC’s science output is scripted and filmed inside the bubble. To the extent that there is ‘communication’ with the world outside the bubble, science is prescriptive of how the world should be, rather than a description of how the material world is.

So the word ‘agenda’ didn’t begin to describe the problem. Everybody, including scientists, has some kind of “agenda”. Agendas are human, as Bronowsky observed. The problem comes in not admitting it, and cementing those agendas into public institutions, away from criticism like some kind of church. It is the bubble which prevents the Royal Society from seeing Ehrlich’s work for what it is, and for asking itself — or being asked — what it is trying to do. And it is the bubble which causes the BBC’s science output to have dumbed down so considerably over the years. As that bubble puts more distance between those within and without, institutional science takes an ever more didactic role, turning its microscope at the disobedient public… “Why won’t you just do what we tell you”.

The Diminished Horizons of Science Broadcasting

The BBC’s flagship science programme, Horizon, is half a century old this year. To celebrate, the Beeb has put seventeen Horizon episodes from the archive online (though these may not be viewable outside the UK). The episodes have been chosen by Alice Roberts, Professor of Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham. Introducing the series, Roberts explains,

It’s fascinating to look at Horizon over its five decades, and to see how the tone of the series changed, reflecting shifting attitudes towards science and technology. The programmes from the 1960s presented a self-assured and optimistic vision of the contribution of scientists and science to society. By the 1970s, the tone had changed, reflecting a growing concern for the environment, and scepticism about science as the answer to all humanity’s problems. In fact, there’s a real sense that technology might even have pushed humanity to the brink of extinction. In Now The Chips Are Down (1978), the invention of the silicon microchip was seen as a threat to jobs: people were about to be replaced by machines.

Roberts makes an interesting point, and one that is made here. The optimism and technological progress of the sixties gave way to a deep pessimism about the future. And it was between these two decades that environmentalism was born. In 1971, an episode of Horizon called ‘Due to Lack of Interest, Tomorrow has been Cancelled’ was broadcast. The film is not available online, though the BBC’s interactive e-book available for Android devices, Kindle Fire, iPad, (Be warned – the ebook is huge, and will eat up a lot of data space and allowance) has a clip from the episode, and a short comment from Professor Iain Stewart, who readers will remember from the awful ‘Earth: Climate Wars’ series back in 2008. However, all we need to know about that episode is this blurb from the BFI.

Looks at the predictions of ecological disaster made by certain scientists, such as Prof. Paul Ehrlich of Stanford University, and examines the extent of the problem and the amount that can and is being done to combat it

Stewart makes the claim that in the 1970s, this was ground-breaking stuff, new to the mainstream. However, the following film made for the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment demonstrates that the environmental movement (such as it was) had mustered political momentum amongst the global political class, not even a year later. The film shows that the environmentalists’ script has not changed in four decades, though fashion and video technology have.

The persistence of that unchanging narrative is one of the most frustrating things about debates about the environment. That’s not to say that Environmental problems do not exist, but that just as there is a difference between a problem such as stubbing your toe, and a problem like being run over by a bus, environmental problems are matters of degree. The environmental narrative is never presented as simply a problem that might cause a problem for some people in some circumstances at some point in the future. It is presented as a total, encompassing, terminal problem facing ‘all of humanity’, requiring immediate and comprehensive adjustments to our way of life, to economies, and political organisation.

Four decades separated the wild claims of Ehrlich from Stewart’s Climate Wars series, with no reflection from Stewart, or the BBC about the failure of the former’s thinking. Yet it would surely have made for a very interesting episode of Horizon. In early 1975, an episode called ‘A Time to be Born‘ raised serious questions about the increased use of medical interventions during childbirth, such as induction of labour, reflecting, as Roberts pointed out, a shift towards a more sceptical view of scientific developments and the role of technology in society. A 1978 film, ‘Now the Chips are Down‘ was concerned with the displacement of actual labour with machines and IT. Even brain surgeons might lose their jobs, warned the Horizon film. If it is right to question the claims made about the medicalisation of childbirth and the automation of the workplace, it is surely right to question science’s ability to formulate the most appropriate (or ‘sustainable’) form of political and economic organisation of society. But British public institutions are even to this day more inclined to celebrate Ehrlich than to raise questions about his failed prognostications.

(One exception here is Adam Curtis’s series, ‘All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace’, especially part two, ‘The Uses and Abuses of Vegetational Concepts’ [watch it here]. The film takes issue with the myth of balance in nature, and the attempt to model society on a false understanding of ecosystems. But although Curtis expertly handles scientific ideas in their contemporary social and political contexts, his films are not part of the BBC’s science output, and his perspective and depth of analysis is not shared by the rest of BBC’s science output.)

Back to Horizon, and Roberts’s introduction. Roberts, notes only that,

Looking back at the films, with the benefit of hindsight, we might feel that some programmes lacked objectivity or balance. But these programmes were reflecting real concerns – concerns expressed by scientists themselves about the potentially negative impacts of emerging technology on human populations, other species, and the planet as a whole. In subsequent series, alongside the presentation of more straightforward subjects such as new discoveries, Horizon continued to deal with areas of concern and controversy. The series accepted that, while science and technology could provide solutions, they could also become a source of problems. This, I believe, is one of the real strengths of this long-running series, and the reason that it is still such a trusted platform. Horizon has brought us astonishing science, and celebrated this important part of our culture, but it’s certainly not just a PR exercise for science. It hasn’t shied away from dealing with difficult scientific questions and public concern about certain aspects of science. It has been investigative and critical, but also thoughtful and non-sensationalist in its approach. It’s a tricky balance to strike, but the producers of Horizon have, over the decades, managed to tackle the subject in a way which has both earned the trust of the public and the respect of scientists.

Roberts is too kind to Horizon’s producers. The BBC, famously, has shied away from difficult questions, and has sought to provoke rather than investigate or illuminate ‘public concern’. I have more questions about the ‘objectivity and balance’ of the more recent episodes than about those from the 1970s.

“This is a film that demands action”, says the voice over of the 2006 Horizon episode on “Global Dimming”. “It reveals that we may have grossly underestimated the speed at which our climate is changing”.

Eight years later, the hiatus in warming is mainstream science, which has no explanation for it. Horizon’s mawkish treatment of the idea of global dimming did nothing to inform the public; its intention was to provoke sensation — not understanding — at the hight of climate change alarmism.

This hints at a transformation of the character of science broadcasting over the years, which the Horizon archive allows us to see more clearly.

In 1996, an episode of Horizon looked at the solution to Fermat’s last theorem. Watch it at the BBC site here or below.

Although I think the film gets slightly more bogged down in the emotional aspect of the discovery than it needs to — especially when considered alongside previous episodes in which scientific developments were considered quite coolly — it nonetheless gets into the process of discovery, and has expectations of the audience — the viewer’s intellectual capacities, as well as his ability to hold his interest even if he doesn’t completely follow the mathematical concepts in question.

A later (2010) episode of Horizon — ‘To Infinity and Beyond’ (watch it at the BBC site here or below) — made a far more feeble attempt to explore a mathematical idea.

BBC.Horizon.2010.To.Infinity.and.Beyond.PDTV.XviD. by singaporegeek

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe…”, says a sinister Steven Berkoff — an actor, seemingly playing the role of either some kind of researcher escaped from another dimension (in which the script from Bladerunner does not exist to be plagiarised by pretentious documentary makers) or infinity personified. “…Things that would change how you see this world. Enough to drive men to madness. … Your intuition is no use here. Faith alone can’t save you. … Is the Earth just one of uncountable copies tumbling through an unending void? … These are the deepest mysteries of the Universe.”

It is bullshit. And it is very silly bullshit. Unlike its earlier counterpart, Infinity and Beyond fails to explore the concept of infinity beyond the prosaic: attempts to formulate a concrete definition of unendingness produces mathematical or logical paradoxes. This could have been the subject for a useful hour long film, but in the hands of the director, it became instead an hour of filler, save for about two or three minutes of insight. It doesn’t explore the development of the concept of infinity and its problems. It put artistic expression — the director’s vanity and self-indulgence — before exposition. It mystified and anthropomorphised the concept of infinity. It failed to explore the debates that exist to any depth. And it made banal, groundless statements with faux gravitas, such as, “If infinity is real, it has implications far beyond the world of science; it strikes at the very heart of what it means to be you”. It doesn’t, you are you, whether or not ‘infinity is real’, whatever that means.

The difference between the two films shows us the triumph of style over substance. The first film required little more than a blackboard to convey complex ideas. The second film uses effects, CGI, a hammy actor, and expensive photography to give an infantile account of infinity. The Fermat film, conversely, gave a clear sense of the development of the discovery in which the personal stories of the participants did not dominate. And and the Fermat film made no extravagant claims about its consequences, in spite of the film-maker’s and participant’s enthusiasm.

Put simply, science as it is conceived of by the BBC’s commissioning editors is not a way of understanding material phenomena. It has become instead something to gawp at in slack-jawed wonderment. It has become a spectacle. The transformation here is in the broadcasters’ expectations of the public. Over the course of 14 years, the BBC’s estimation of its audience diminished.

So what. We’re talking about popular science, after all. Who cares if science broadcasting got a bit naff after the 1990s? This isn’t the point. The point is that the broadcasters’ attitude to the viewer has changed, which may only be disappointing to those of us who expect more out of public service broadcasting. And this attitude persists in films that are more significant to public debates.

And it gets worse.

Another film chosen by Alice Roberts to be in the Horizon collection was Paul Nurse’s attempt to explain what he saw as ‘Science Under Attack’. (Watch it here).

There is not much to add to what I pointed out at the time: