The Apollo Lords – Shooting for the Stars? Or the Foot?

The climate debate has seen much history dragged into the present, to be served up again as hollow pastiches in environmentalists’ and climate activists’ shallow morality plays. Unable to make their own history, greens have to recycle moments from the past, to give their cause historical significance in the present. There have been green ‘New Deals‘. Martin Luther King’s words were altered to make a green message — a climate ‘fierce urgency of now‘. There have been comparisons of abolition with mitigation, allowing academic activists to claimt that climate sceptics were the latter day moral equivalent of slave traders. Some activists have gone further than mere figurative allusions, and dressed themselves up as ‘climate suffragettes‘. But my favourite has been the “climate change is our moon landing”, beloved of erstwhile UK chief Science Advisor, David King.

Kennedy’s famous moon landing speech outlined the ambition to put men on the moon within a decade. And so it is no surprise that a decade is the time frame chosen by the latest venture to bear King’s name…

King is one of six climate aristocrats — the others are all Peers — that have put together the ‘Global Apollo Programme’ (GAP), which wants the same proportion of GDP spent by each member country as the US spent on its own moon-shot.

The top table of Gap is as follows.

Sir David King, Former UK Government Chief Scientific Adviser. Lord John Browne, Executive Chairman at L1 Energy. Former President of the Royal Academy of Engineering and former CEO BP. Lord Richard Layard, Director of Wellbeing Programme, LSE Centre for Economic Performance. Emeritus Professor of Economics. Lord Gus O’Donnell, Chairman, Frontier Economics. Former UK Cabinet Secretary. Lord Martin Rees, Astronomer Royal and Former President of the Royal Society and Master of Trinity College, Cambridge & Emeritus Professor of Cosmology and Astrophysics. Lord Nicholas Stern, IG Patel Professor of Economics and Government, LSE, & Chair of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. Lord Adair Turner, Senior Research Fellow, Institute of New Economic Thinking & Former Chairman of the Financial Services Authority and the Committee on Climate Change.

This blog has never objected to increased emphasis and budgeting on energy R&D. Contrary to the comments made about energy by notable environmentalists, more energy is a good thing…

“It would be little short of disastrous for us to discover a source of clean, cheap, abundant energy.” — Amory Lovins

“Giving inexpensive and abundant energy to Americans today would be like giving a machine gun to an idiot child.” — Paul Ehrlich.

Environmentalism, it is argued here, has always been, and is necessarily about locating political authority in a particular view of humans, society and its relationship with the natural environment. Abundance, or even just the promise of abundance, is anathema to that view. Even abundance in the abstract sense divorces us from nature. A theological comparison pertains here with The Fall. The limits of nature are there to discipline us, to constrain our vices, and to impose the order that our sins turn to chaos.

On the optimistic, humanist view, however, more energy is a good thing precisely because it frees us from such limits which invariably result in suffering. But abundance threatens the political order imagined by today’s secular ascetics. So it is a surprise to see the leading proponents of far-reaching climate malthusianism now openly calling for R&D.

The question that needs to be asked about any claim for R&D expenses, though, must be ‘what for?’. Energy R&D is not a good thing in-and-of-itself. Energy is a Good Thing for us. The new Global Apollo Programme seems to want energy to be for the climate.

The contradiction here is one that the GAP cannot understand. It sounds great, to find a source of energy which is as cheap as coal within a decade. But this would be no leap equivalent to landing on the moon, because it would not yield any benefit to us greater than burning coal. Moreover, the same R&D budget not restricted to the green sector might create the possibility of new sources of fossil fuels. It might accelerate the exploitation of methane hydrates, for instance. Or it could help in the development of techniques like underground coal gasification. Or fracking, of course. Restricting R&D to ‘green’ technology could conceivably carry the consequence of precluding such developments which would make fossil fuels more abundant and less expensive, thereby denying those who would benefit from it the advantages of any new technology. The best that GAP offers us is life a decade hence as good as today.

The report produced by GAP claims that

One thing would be enough to make it happen: if clean energy became less costly to produce than energy based on coal, gas or oil. Once this happened, the coal, gas and oil would simply stay in the ground. Until then fossil-fuel-based energy should of course be charged for the damage it does, but ultimately energy should become able to compete directly on cost. How quickly could this happen?

The challenge is a technological one and it requires a major focus from scientists and engineers. The need is urgent. Greenhouse gases once emitted stay with us for well over a century. It would also be tragic if we now over-invested in polluting assets which rapidly became obsolete.

In the past, when our way of life has been threatened, governments have mounted major scientific programmes to overcome the challenges. In the Cold War the Apollo Programme placed a man on the moon. This programme engaged many of the best minds in America. Today we need a global Apollo programme to tackle climate change; but this time the effort needs to be international. We need a major international scientific and technological effort, funded by both public and private money. This should be one key ingredient among all the many other steps needed to tackle climate change which have been so well set out in the latest reports of the IPCC.

On GAP’s view, finding a technology to exploit renewable resources such that they become as cheap as coal is nothing more than just scientific investigation. But what if such a discovery were never possible? What if it turns out that it is, after all, harder to turn ambient energy into useful energy than it is to turn energy-dense substances into energy?

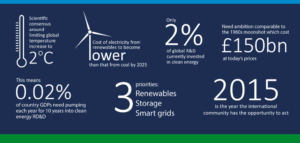

The key to this miraculous discovery lies in another chart produced by GAP.

I love these charts, because they mean absolutely nothing. What are the pillars supporting? And in what sense are storage, transmission and efficiency ‘foundations’ for the pillars? They would make more sense if they were labelled, ‘Sunday’, ‘Monday’, ‘Tuesday’ from the bottom, followed by ‘Wednesday’, ‘Thursday’, ‘Friday’ across. Says the GAP,

For three of these six areas (which are shaded in the diagram) there is already a high level of research effort. For example, in nuclear fission there is the G4 international programme to produce a much more efficient use of uranium whereby enrichment occurs on site; in nuclear fusion there is the International Thermonuclear Energy Reactor (ITER) programme. But in the three unshaded areas (renewables, storage and transmission) there is far too little research and the present proposal focusses on those areas.

But how true — or significant — is this?

Figures from the OECD and IEA seem to bear out the proportions. (I haven’t been able to locate the precise amounts of funding). (There seems to be some data missing from the series, and the reduction in funding may be a result of quality. Also, I am assuming that this is government expenditure, not including private funding of R&D).

But think about what is being produced here. The proof of concept of a new solar PV cell would fit in your hand. But a proof of concept for nuclear fusion or fission would likely require a great deal more hardware, real estate infrastructure and thus capital, just to get off the ground. For this reason, also, state funding of R&D might be filling a gap in nuclear, so to speak, which potential developers could close for themselves in the storage and solar sectors. GAP’s comparison might not be one of apples and apples.

Moreover, if there is an urgent need to address the problem, in what way is the $5 billion of global R&D budget for nuclear energy ‘enough’? It wouldn’t even be enough to build a nuclear power station. Given that Nicholas Stern — one of the leaders of GAP — imagines a world in which climate change costs integer percentages of global GDP, and argues for similar expenditure or opportunity cost on mitigation, it hardly seems like a sensible claim. Even more so, when we consider that energy storage will always add a cost to generation, and that generation of power from renewables might never compete with coal. Einstein’s equation, on the other hand, tells us what the material limits of yield from nuclear reactions are, and they are astronomical compared to even the most optimistic expectations of yield from renewable energy.

Again, this isn’t a throw-all-the-money-in-the-world-at-nuclear-R&D argument, mainly because I don’t believe the premises of GAP, that climate change is the urgent problem that Stern et al have claimed. But there is a better argument for investing in energy R&D for the good it will produce for people. And if climate change is an urgent problem, why spend such a paltry amount as $150bn a year on it? Why not spend as much on energy R&D as was spent on banking bailouts and quantitative easing throughout the Western world?

One answer returns us to the political utility of scarcity. In short, GAP is a manifesto for climate bureaucrats, and the promise to them is that they will be able to sustain their cake and eat it. It is only by making modest proposals, rather than by making promises of the deadly abundance, that the climate establishment can maintain its grip over the political agenda. The clue is in the programme:

(1) Target. The target will be that new-build base-load energy from renewable sources becomes cheaper than new-build coal in sunny parts of the world by 2020, and worldwide from 2025.

(2) Scale. Any government joining the Programme consortium will pledge to spend an annual average of 0.02% of GDP as public expenditure on the Programme from 2016 to 2025. The money will be spent according to the country’s own discretion. We hope all major countries will join. This is an enhanced, expanded and internationally co-ordinated version of many national programmes.

(3) Roadmap Committee. The Programme will generate year by year a clear roadmap of the scientific breakthroughs required at each stage to maintain the pace of cost reduction, along the lines of Moore’s Law. Such an arrangement has worked extremely well in the semi-conductor field, where since the 1990s the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS) has identified the scientific bottlenecks to further cost reduction and has spelt out the advances needed at the pre-competitive stages of RD&D. That Roadmap has been constructed through a consortium of major players in the industry in many countries, guided by a committee of 2-4 representatives of each main region. The RD&D needed has then been financed by governments and the private sector.

Look at how quickly we skate through such petty little detail as how, in the space of just five years, this project will make solar power cheaper than coal in sunny countries, and how simple it will be for countries to join. But then look at how much detail there is about the committee, as it effortlessly reproduced Moore’s Law in an entirely different technology sector, as though laws such as Moore’s simply by designing the right institutional configuration.

Would we be surprised to find the names King, Browne, Layard, O’Donnell, Rees, Stern, Turner on this committee? They seem to be the names on almost every other climate boondoggle going?

The tone of the GAP’s report seems incredulous that the world has not already handed over all its cash to these six knights and peers of the realm.

We are talking about the greatest material challenge facing humankind. Yet the share of global publicly-funded RD&D going on renewable energy worldwide is under 2% (see Table 1).18 19 Remarkably the share of all energy research in total publicly-funded R&D expenditure has fallen from 11% in the early 1980s to 4% today. This is a shocking failure by those who allocate the money for R&D.

But hold on a minute, my Lords… Who, free from the excesses of party politics and democratic contest, has been in a position to advise governments on the best strategies to dealing with climate change? Your noble selves, that’s who. In fact you were appointed in precisely this capacity. But as yet, it has taken you decades to organise an effort to orient publicly-funded research.

There is no doubt that David King has argued for different research priorities. Here he is in 2008, arguing with Brian Cox, who later became as disappointing as King, for his misapprehension of the climate debate (amongst other things, including his religious conception of ‘science’).

As reported here at the time, King was jealous of the budget’s available to high-energy physics, its international profile and its superstar status. Particle physics is sexy, whereas people who bang on about climate change invariably express themselves in a nasal whine, and in contrast to the optimism of their counterparts in physics, are preoccupied with the negative implications of their science. King, for example, saw the search for the Higgs-Boson as so much ‘naval-gazing’, without useful application in a world at the brink of catastrophic change — a burden that he seemed to be shouldering all by himself, while others toyed with expensive hardware. Never mind the possibility that the work at Cern might produce insight useful for the development of nuclear energy.

King’s colleague at GAP, Martin Rees, takes a similar view of inappropriate scientific research priorities, as has been discussed here before. In Our Final Hour, Rees outlines his scare stories, amongst which are his estimate that the odds of the human race surviving this century are just 50%, and that by 2020 — five years into the GAP project — “bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event“. It was, after all, science which unleashed all that carbon. Science’s bureaucrats, then, are very good at making work for themselves.

Science has been very good, then, at telling us about what we must not do. But not so good at providing solutions to the problems its leading lights claim to have identified. As Climate Change Committee (CCC) member, Julia King, admitted, the CCC saw behaviour change as a key strategy in reducing emissions. Odd words, for a professor of engineering — unless it is behaviour she wants to engineer. And that seems to have been the emphasis of climate bureaucrats. As was pointed out in Rob Lyons’s interview with Bjorn Lomborg a few years ago, ‘Climate change: a practical problem, not a moral one‘. Said Lomborg,

If you do the standard Kyoto-style solution […] you do a couple of pence worth of good for every pound that you spend. But if you spent that same pound on energy R&D, you’d avoid £11 worth of climate damage – that’s 500 times more benefit. That’s why I’m suggesting we should be spending real money on tackling climate change, but we should be spending it smartly not stupidly.

But, of course, abundance creates a scarcity for the climate bureaucrat, who now scratches around for justification. It has taken so long for the climate change establishment to recognise the relatively strategies advocated by the likes of Lomborg, Pielke and the Breakthrough Institute because their ambition of creating a global political climate institution has been so long in its collapse. Political reality has caught up with environmentalism’s ambitions, and it is only now that the policy-down approach looks like it is about to collapse that the technology-up approach, seems to be gaining traction, and that the likes of Stern et al are pretending it was their idea all along.

It would not have been hard for the technology-up approach to have succeeded where the ambitious one-size-fits-all global policies have utterly failed. Financing R&D through microtaxes on energy consumption would have made some complain about the necessity of such a project, and the rights and wrongs of state intervention in innovation. But it would have been hard for those complaints to say that any real harm would come of it. Instead, climate sceptics can point to actual harm. There have been two decades of re-emphasis in the development agenda, which may have deprived millions of people access to energy, and increased energy costs in more developed economies, making life harder for millions of poorer families, and depriving many more of opportunity. We can compare the consequences of anti-technology (and in many instances, anti-human) policies to the emerging reality: that stories of climate catastrophe were simply overcooked, and intended to give momentum to a political project; that the implications of climate change are not as urgent as other problems faced by very many people; that development (not even ‘adaptation’) , including access to cheap energy, would be a better remedy to any likely perceivable consequences of climate change than radical mitigation; that hasty mitigation is itself harmful.

These things now being understood is a demonstration of the GAP project’s moral bankruptcy. We are supposed to take at face value the good faith of these six men. But in fact this latest move looks much more like six climate bureaucrats hedging their bets ahead of failure at Paris, and the shifting of the climate agenda.

If that sounds like I’ve over-egged the point, consider the concluding paragraphs from the Guardian’s coverage of GAP’s launch…

Sir David Attenborough, who recently discussed climate change in a meeting with US president Barack Obama, said: “I have been involved in arguments about the despoilation of the natural world for many years. The exciting thing about the [Apollo] report is that it is a positive report – at last someone is saying there is a way we can do things.”

Prof John Schellnhuber, a climate scientist and former adviser to German chancellor Angela Merkel called the Apollo plan “truly ingenious” and said it “could well be a tipping point” in tackling climate change.

Is it conceivable that such learned figures such as Attenborough and Schellnhuber didn’t know of the existence of this form of idea — of spending around $15bn a year on energy R&D? Did they miss Lomborg’s book and film, “Cool It” — which contain much more detail than the GAP report? Or Pielke’s and the BTI’s volumes of work on the same theme? If it is true that they’d never considered the possibility before, it speaks to their bad faith nonetheless. They have no place commenting on climate change if they are new to this idea of solving the problem of climate change through technology. And so it is with the six knights and lords, who make no mention of Lomborg, either.

Tim Worstall puts it most succinctly:

These people are idiots, aren’t they?

Everyone and their grandmother knows that if you can design, invent or kludge together something that either:

Generates electricity cheaper than coal

or

Can store intermittently produced electricity cost effectively

…then you’re likely to become the world’s first dollar trillionaire. It’s, how to put this, uncertain, that any more incentive is needed.

Idiots, they surely must be. In fact, doesn’t this story of a King, and his defenders of the Realm in search of the Holy Grail sound awfully familiar?

The Global Aoollo Programme arrive at the COP meeting in Paris…

Shock News: Guardian Pages Sponsored by Rank Hypocrisy

Two things have become clear to me over the years regarding the putative ‘ethics’ of the Guardian’s green campaigns, copy and hacks.

First, it is a general rule that ‘ethics’ are for thee, but not for me. Second, these ‘ethics’ are intended to elevate those who bear them.

The people who bang on the loudest about ‘ethics’ are usually the least observant of these ‘ethical’ principles. It is not uncommon to find the climate Great and Good — celebs like Leonardo di Caprio and Pharrell Williams — preaching climate change to the World from the comfort of a private jet or luxury yacht. ‘Ethics’ gives a platform, from where to judge.

For the Guardian, the two limitations of its ‘ethics’ mean that it can weave an article out of nothing but the alleged infraction of an “ethic”, while in fact being in the midst of something far worse.

In today’s Guardian, Terry Macalister — the paper’s energy editor — writes

Shell sought to influence direction of Science Museum climate programme

Oil giant raised concerns one part of the project, which it sponsored, could give NGOs opportunity to open up debate on its operations, internal emails show

The article is published as part of the newspaper’s Keep it in the Ground campaign against fossil fuel companies, encouraging big capital investors to move their interests out of brown energy — ‘divestment’. The allegation is that Shell, as long-time sponsors of the Science Museum in London may have used this funding relationship to change the messages delivered by the museum’s climate change exhibit.

I visited the museum a few years ago, and wrote it up for Spiked. Read it here. Most notable, I felt, was the reflection of the times across the Museum’s different galleries. All those artefacts of historical pioneering spirit — spacecraft, aircraft, instruments and machines — were now lost to bland interactive displays.

The contrast between the space race and today’s low aspirations epitomised by Atmosphere invites a further comparison of the prevailing ideologies of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries and their propaganda. For all the world’s deep and dangerous problems that belied the optimism surrounding the Apollo programme, and of Sputnik and Yuri Gagarin’s missions, they remain uplifting reminders of what is possible. The contemporary preoccupation with climate change, on the other hand, yields only joyless propaganda: an antithesis to the progress promised in the past.

Here’s some video I took of the same.

It was, as I described it, a tedious dollop of eco-propaganda. If there was any influence of fossil fuel companies’ dirty money on the exhibition, it certainly wasn’t obvious to me. The exhibition was, in spite of being sponsored by oil companies, as glib and alarmist as any propaganda issued by green NGOs.

Yet the Guardian claim…

Shell tried to influence the presentation of a climate change programme it was sponsoring at the Science Museum in London, internal documents seen by the Guardian show.

Epitomising this weird new puritanism, ex-academic and Guardian blogger, now at the failed 10:10 campaign, Alice Bell tweeted,

Neat bit of FOI digging reveals Shell tried to influence direction of Science Museum climate programme they sponsored http://t.co/ba2lav4JQU

— Alice Bell (@alicebell) June 1, 2015

Not a one off. Seen BP PR docs boasting about the role they played in the Sci Museum's Energy gallery, backed up w quotes from museum staff.

— Alice Bell (@alicebell) June 1, 2015

People have laughed at me for years for caring about this issue, so nice to see make a front page. Might even buy a dead tree copy today!

— Alice Bell (@alicebell) June 1, 2015

Exactly a year after my Spiked article on the exhibition, Bell seemed to agree…

So, exceedingly pretty as Atmosphere is, the highlight of my trip to the museum was gawping at the Apollo 10 capsule. A humble-looking object, it has actually been around the Moon. You can see scorch marks from when it re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere.

I thought about its history, and the many times I’d stood there before. I remembered conversations I’d had with people about it. I remembered being moved to read more about the history of space travel, including the ways images from Apollo missions had inspired green activism in the 1970s, presenting Earth as a fragile, beautiful and, indeed, blue sphere in space.

Time spent quietly pondering the history of an object is an old-fashioned idea of a museum, but it still has power.

She’s wrong, though, of course. What inspired the ‘green activism’ of the 1970s was not as much pretty pictures of ‘Gaia’ as much as it was the oil shock, and the other economic and Cold War crises that developed as the postwar economic boom turned to bust. And it was not ‘green activists’ which were inspired as much as billionaires and their lackeys, who formed around the Club of Rome, and influenced the UN. Bell re-writes environmentalism’s history. Many, many many more young minds were inspired by the possibilities that the moon landing represented than were moved by the lonely image of the earth in Space. The green movement’s half-century campaign for austerity has sought to deny those possibilities to those minds.

I digress. The point here is that the Atmosphere exhibition at the science museum, clearly wasn’t some kind of fossil-fuel propaganda. Nobody taking the exhibition at face value could walk away from it as a climate change sceptic. Not even Alice Bell was complaining in 2011 that there was any hint of scepticism or denial in the exhibition. Her criticism was, like mine, that the fashion for interactive displays and the suchlike, as a way of attempting to engage minds with the ‘issues’ is probably not adequate.

The only way it would be possible to see Atmosphere as serving fossil fuel interests would be if one were to reflect on just how naff its exhibits and messages were, and what thinking and relationships may have been behind it.

Take this utterly clichéd House of Cards artwork, for instance. If we see it as an ironic gesture, then, yes, perhaps we can see that it could come to epitomise everything green: an art project that is entirely without artistic merit is commissioned by a public organisation with mixed private/public funding, as part of a broader, policy-relevant exhibition; an otherwise talentless ‘artist’ supported by a public organisation. Or perhaps the plan was simply to bore people away from the issue.

Where are the crappy paintings by climate sceptics at this Shell-sponsored exhibition? Where are the second-rate interactive media installations giving the sky-dragon version of climate change physics at this fossil-fuel industry funded show? And where are the glib ‘messages’ moderating — let alone ‘denying’ — the alarmist narratives served up at this Big Oil beano? If Shell or its PR firms intended to use Atmosphere to serve its own interests in the climate debate, it should be thoroughly ashamed of itself… Not for the shame of seeking to intervene in this way, but because it has done such a pisspoor job of it.

So what is behind the headlines? This picture of an oil company’s massive, illegitimate intrusion into the public debate on climate change, you will notice, is painted with run-of-the-mill Guardianista weasel words… “The Anglo-Dutch oil group raised concerns with the museum…”, “The company also wanted to know…”, “Emails show the close relationship between the Science Museum and Shell…”, “… a Shell staff member gives what they call a “heads up” on a Reuters story…”, “…a Shell employee [has] some concerns [that an] exhibition […] creates an opportunity for NGOs to talk about some of the issues that concern them around Shell’s operations.”

Is this the stuff of a conspiracy? Raising concerns? Are “close relationships” between major funders and beneficiaries unusual? Or is it just innuendo?

Perhaps one complaint — that “Shell’s own climate change adviser – former oil trader David Hone – made recommendations on what should be included” — might have been more interesting, had the exhibition not been, as discussed above, a virtual playground for climate alarmism. But there was no sign of scepticism of either climate science or policy on show.

Similarly, the Guardian suggests that the museum is compromised because its director criticised Greenpeace… (HOW DARE HE?!!).

the Science Museum’s former director Chris Rapley criticised Greenpeace’s successful campaign to make Lego drop its partnership with Shell.

But this, neither, passes the smell test. While this conspiracy between Shell, the Science Museum and Rapley was going on, he was penning his awful monologue, 2071, which I reviewed for Brietbart London back in November.

If you really want to know what this stage play formula is like, imagine a compulsory lecture on climate change at a low-tier university. On Saturday night. With Powerpoint. A city… no a world… of better offers exists outside. But you are trapped.

This is no exaggeration. Chris Rapley is keen to qualify his role as lecturer by professing his expertise in many things during the opening ten minutes (they felt like hours). One of those things is the cryosphere (the frozen parts of the planet), which is so-called because Rapley went there and bored entire mountains of ice to tears.

Rapley has since given up his snow mobile. Now he sits in a chair, from where, almost motionless, he freezes the brains of hundreds of people, each of whom seem to have volunteered themselves for this 70 minute ordeal of skull-crushingly dull ‘untertainment’ for up to £32 each. By the end of its ten-day run, some 3,600 individuals will have witnessed Rapley’s sedentary call to action.

Yet Naomi Klein Tweeted…

Amazing piece in @guardian about Shell trying 2 silence climate debate in a museum it sponsors #keepitintheground http://t.co/CjOaXRVuI3

— Naomi Klein (@NaomiAKlein) June 1, 2015

If Chris Rapley is part of some conspiracy to ‘silence the climate debate’, much less undermine climate science and subvert climate policy, he has me completely fooled. I am totally and utterly hoodwinked by his clever act. I have been to the climate change exhibition at the Museum he was director of. And I have been to see his stage play. And I have seen him speak at about half a dozen debates. I remain unimpressed by his argument and intellectual depth, but I am convinced he is a believer. He has bored me to tears, and I’m sure he has done it for his own self-interest, but I am sure he believes, nonetheless.

It is perhaps significant that the Guardian article does not reveal who obtained these emails. Because reading them reveals absolutely nothing underhand at all. See for yourself. https://www.dropbox.com/s/ddz2fg9vwzt7x31/shell%20science%20museum%20foi%20-%20highlights.pdf?dl=0#

But another reason for the Guardian’s coyness is that the campaign which obtained the email exchange between the Science Museum and Shell wants to use the fact of sponsorship to embarrass the museum into dropping the sponsor. That campaign is BP or not BP, whose aim is to disrupt oil companies’ sponsorship of cultural events, as this video shows.

An interesting aside… The chap at 0:52 introduced as “Danny”, AKA Danny Chivers. Chivers appears to be the PKA Tim Lever, spokesman of the 2007 Climate Camp. Here he is, talking to Richard and Judy…

Clearly disrupting mass transport left Timmy and his pals more alienated from an unappreciative audience than they were anticipating. Better to target the luvvies, by disrupting instead subsidised and sponsored performances of Shakespeare. This demonstrates a considerable adjustment of the radical environmental movement’s ambitions over the last few years: from disrupting operations at one of the busiest transport hubs in the world… To heckling at a play, to an audience who likely already shares their values, and whose minds did not need changing.

If there is any constituency in the world that needs no encouragement to participate in a shallow Two Minute Hate ritual against oil companies, it is the luvvies — whose lifestyle choices are, broadly speaking, subsidised on the basis that they are Good Things. And it is this which most reflects the utter absurdity of the campaign. As the BP-or-not-BP campaign’s own video shows, nobody was fooled by BP’s sponsorship of the arts — its greenwashing. And so it is equally unlikely that anyone coming away from the Atmosphere exhibition would, even if they had noticed Shell’s sponsorship, have come away from it thinking about what a thoroughly decent Big Oil company it is.

BP-or-not-BP are concerned that people might not understand, you see, that companies which sponsor cultural things… Things like museums, operas, and plays… Do bad things, like producing energy for things like, erm, museums, operas and plays, as well the vehicles which take people to them, and things such as schools, hospitals and… Horror of horrors… factories where things are made. BP-or-not-BP want to rid the cultural sphere of companies like BP and Shell, not because they can point to any substantive interference intended to sway opinion in the climate debate, but because they believe that by purging the cultural sphere, the debate can be won. Think of it as Ethical Cleansing…

This brings us to why the Guardian omitted the FOI requesters… Their divestment campaign now in full swing, it would be a foolish time to admit to the world that there is something hypocritical about campaigning to ‘Keep it in the Ground‘ at the same time as being sponsored by the third largest coal mining interest in the world.

The very same Guardian writer has written articles under that very same campaign, saying that “Oil companies’ sponsorship of the arts ‘is cynical PR strategy’“. But just a couple of clicks away is the Guardian’s Anglo American partner zone section of its Sustainable Business pages, the most recent article on which was published just two days ago.

This is first-order, Class-A hypocrisy, of course. There is nothing that any Guardian journalist can say about Shell’s sponsorship of the Science Museum, or its climate exhibitions. There is no way the Guardian can continue to campaign to ‘keep it in the ground’. And there is no way it can criticise any organisation for being secretive about its arrangements, or for failing to respond to what it demands are ‘ethical’ imperatives.

So much for the Guardian’s climate ‘ethics’, then. That paper demonstrates that ‘ethics’ don’t apply to itself. Its own ethical cleansing campaign has, for years, consisted of endless stories about links between oil companies, policy-makers and public organisations, dominating the debate. But these were so many stories about next-door-neighbour’s-cousin’s-cat-who-one-knew-a-man… Take this graphic from the Guardian’s campaign. What’s missing?

The answer is the name and logo of the Guardian’s own sponsor, Anglo-American. They seem to have bought The Guardian’s silence. A bigger scandal, surely, than Shell sponsoring a climate-change exhibition.

Beyond the Graun failing to meet the standards it sets for others, though, is a sadder picture. The Science Museum’s former director, Chris Rapley, for instance, caught between a rock and a hard place. And Shell themselves, of course, trying to do the right thing in the era of corporate social responsibility.

A plague on all their houses. They invited it. Rapley chose to use the Science Museum as a vehicle for environmental politics. And Shell stumped up the ready money, for whatever ends. They wanted to champion climate change, but have been caught out and called out by the very movement they were seemingly hoping to capture. Shell, for instance, are sponsors of the Green Alliance (see their list of partners here), which coordinated the recent cross-party consensus on climate policy ahead of the recent UK general election. Where was the outrage, the direct action, and the Grauniad innuendo?

If Rapley, the scientist was worth an iota of his public profile, he would have been far more critical of the environmental movement, and he would have been critical of it long before it campaigned to get Lego to pull out of a deal with Shell. And Shell themselves, rather than lavishing money on green NGOs and lobbying outfits would have spent its money more wisely if it had spent a few quid on challenging the nonsense that its beneficiaries publish routinely… Including that daft exhibition at the Science Museum.

What are these kind of ‘ethics’, anyway? The Islamic State has ‘ethics’. The Taliban has ‘ethics’. They too seek to purge culture of infidels. And, as the Mirror journalist put it, they will brook no dissent. But behind these ‘ethics’ are naked self-serving ambitions to control society. That is what ‘ethics’ are in today’s world. They are not a form of knowledge, to which we all have access, to measure the rights and wrongs of actions, but are diktats, issued by self-appointed authorities for their own ends.

Identifying 'Lukewarmism'

Over at the Making Science Public blog, Brigitte Nerlich wonders about the origins of the word ‘lukewarmer’…

As I am interested in the emergence and spread of various labels used in the climate change debate, such as for example ‘greenhouse sceptic’, I wanted to know more about the label ‘lukewarmer’ and while I can’t write its history in this post, I can show how it was used in the news. I put ‘lukewarmer’ and ‘climate’ as search terms into my preferred news data base, Lexis Nexis, on 3 May 2015 in All English Language News and got (only) 43 results. There were 8 duplicates. So, in the end I read 35 articles, published between 30 January 2010 and 22 April 2015. Compared to the use of other labels, such as denier and alarmist for example, these are small numbers. What follows are extracts from this small body of articles and I’ll leave it to readers to draw their own conclusions.

Underneath Brigitte’s post is a long, unproductive exchange between various contributors and astronomer Ken Rice, pka And Then There’s Physics, who runs the blog of the same name. Rice bans alternative opinion from his own blog, but is a prolific commenter — so much so it’s hard to wonder how he gets any astronomy done — at popular blogs. Lucia made a heroic attempt to explain to Rice that there are more than two positions in the debate — read her précis here — but to little progress, such is the limit on dialogue imposed by the astronomer’s personality or capacity, it’s not clear which.

What is interesting about the phenomenon of ‘lukewarmism’ is its background. More respectable than climate scepticism and climate denial in turn, of course, but seemingly positioned just as far away from climate alarmism. But in this sense, anyone seeking to identify themselves as ‘lukewarm’ needs to take for granted the categories that others designate for themselves and each other, to triangulate their own coordinates.

But didn’t this space always exist? Was it only discovered recently? In the discussion at Making Science Public, various attempts are made to identify positions in the debate with respect to estimates of climate sensitivity. If this be the index corresponding to the fundamental axis of the debate, then, why not just give everyone on it a number? Deniers, 0-0.5; sceptics, 0.5-1.0; lukewarmers, 1.0 – 2.0, warmists 2.0-3.0, alarmists 3.0-99999999999.0.

Such an index would tell you nothing about why somebody believes that the climate’s sensitivity is what they believe it to be, much less why that number is significant. The numbers would obscure the argument, and in turn would prefigure the debate. This is, of course, the point of Consensus Enforcement that Ken Rice and his highly prolific associates engage in. Many a lukewarm blog — and even many ‘denial’ websites — has been all but colonised, lest the climate debate be contaminated by nuance. The consensus enforcers don’t even want there to be an index — admitting to an entire axis of perspectives would make the debate far more complicated than the simple matter of right-vs-wrong, good-vs-bad or science-vs-denial that they want it to be. The point of consensus enforcement is to sustain the polarised account of the debate.

Of course something approximate to the lukewarm position has always existed. And as the recent hand-wringing about Bjorn Lomborg’s appointment, and subsequent dis-appointment at the University of Western Australia shows, the debate has at least one more axis than even the enforcers admit to. In the Guardian, consensus enforcer, Graham Readfearn claimed of the affair, “The spark was the University of Western Australia’s decision to back out of a deal to host a research centre fronted by climate science contrarian Bjørn Lomborg and paid for with $4m of taxpayer cash.”

The designation of the category ‘climate contrarian’ to Lomborg is an interesting one, as Lomborg himself takes a fairly mainstream view of climate science, and stresses the need to decarbonise the energy sector. It is true that he says this is not the world’s greatest problem, but this is hardly ‘contrarian’, except in the world imagined by the consensus enforcers, where any policy short of radical mitigation is merely a lighter shade of ‘denial’. The case of Lomborg’s treatment at the hands of the consensus enforcers is the most perfect demonstration of their polarisation of the debate — the lumping together of lukewarmers, sceptics and deniers.

The same University was home to Stephan Lewandowsky, who has set up camp in the West of England — Bristol University — from where he has famously pronounced on the apparent correlation of conspiracy theories and climate change scepticism, which was fatally flawed and widely debunked, and led to a retraction. Lewandowsky has now teamed up with Naomi Oreskes, to produce a new theory of the climate debate, called ‘seepage‘,

… we argue that the appeal to uncertainty in public discourse, together with other contrarian talking points, has “seeped” back into the relevant scientific community. We suggest that in response to constant, and sometimes toxic, public challenges, scientists have over-emphasized scientific uncertainty, and have inadvertently allowed contrarian claims to affect how they themselves speak, and perhaps even think, about their own research. We show that even when scientists are rebutting contrarian talking points, they often do so within a framing and within a linguistic landscape created by denial, and often in a manner that reinforces the contrarian claim. This “seepage” has arguably contributed to a widespread tendency to understate the severity of the climate problem (e.g., Brysse et al., 2013 and Freudenburg and Muselli, 2010).

According to this theory, the global warming ‘hiatus’ is a myth, put about by climate sceptics, but which has been absorbed by climate scientists (as per ‘meme’), who reproduce it blindly, having been so beaten and harassed by the assembled forces of contrarianism and denial. But Richard Betts disagreed.

The authors suggest that climate scientists are allowing themselves to be influenced by “contrarian memes” and give too much attention to uncertainty in climate science. They express concern that this would invite inaction in addressing anthropogenic climate change. It’s an intriguing paper, not least because of what it reveals about the authors’ framing of the climate change discourse (they use a clear “us vs. them” framing), their assumptions about the aims and scope of climate science, and their awareness of past research. However, the authors seem unable to offer any real evidence to support their speculation, and I think their conclusions are incorrect.

Betts’s rejoinder was published as a guest post at… of all places… Ken Rice’s blog, where it was received by a mixture of responses, most resistant to the nuanced picture of the debate advanced by Betts. The post was republished at WUWT. I’m curious, though, why Richard Betts didn’t publish it on one of the websites of the organisations he is associated with, such as the Met Office. After all, Lewandowksy takes aim at climate scientists and their work directly. (For more comment, see also contributions from climate scientists including Betts in the comments under the article at http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/may/15/are-climate-scientists-cowed-by-sceptics )

And this point is worth more consideration. As I’ve argued before, “memes” — a theory which often comes up in the climate debate — are a double-edged sword. Lewandowsky is saying that climate scientists are vulnerable to ‘contrarian memes’ about ‘the pause’. But if this is so, wouldn’t climate scientists be equally vulnerable to ‘warmist memes’ and ‘alarmist memes’? After all, the warmist cause is so much better funded, and able to mobilise vastly more resources than any climate sceptics.

Once we start to see debates in terms of competing memes, we reduce all notions of truth to merely a dominant ‘meme’. Which is to say ‘truth’ might be nothing more than a meme — an arbitrary judgement which merely reflects dominant beliefs, not necessary truth. If that still sounds too theoretical, consider that it is precisely what Lewandowsky, Oreskes et al have done. They have said that the entire scientific community — individual scientists, scientific institutions, and the IPCC — were vulnerable to the ‘meme’, whereas only the historian of science and the psychologist were immune to its propagation through the very community that both Oreskes and Lewandowsky claim has produced a robust, unimpeachable consensus. Indeed, science itself — as a process — is no longer the best test of theories about the material world. And science — as an institution — is no longer an authority on any matter. All because us crafty deniers, by careful deployment of a simple word — “hiatus” — were able to undermine the consensus on climate change, and to hijack the entire global research enterprise.

Moreover, the implication of Lewandowsky and Oreskes is not only that by virtue of their vulnerability they are incompetent, climate scientists cannot even research ‘contrarian memes’, because to research the meme in question is QED to become vulnerable to it, and to reproduce it: ‘seepage’.

This returns us to the post at Making Science Public. Brigette opens by referring to a recent post by Tamsin Edwards, who is to the ‘contrarian meme’ what Typhoid Mary was to, erm, typhoid…

On 3 May Tamsin Edwards wrote an article for The Observer entitled “The lukewarmers don’t deny climate change. But they say the outlook’s fine” (see here for a discussion; I should point out that Tamsin didn’t choose the title for this article).

I find Edwards writing for the Guardian as odd as Betts writing for ATTP. Indeed, the comments beneath her article reflect the preference for shrill, alarmist copy, not nuances. Ditto, and moving more into the established Lukewarm camp, Roger Pielke Jr, recently had an article on the same website, ‘Why discrediting controversial academics such as Bjørn Lomborg damages science‘. The very first comment is from Ken Rice, who takes the moniker ‘fast fingers’ from Bob Ward…

What would probably help is if someone like Lomborg where to acknowledge the errors he makes when talking about something like climate science.

… Which is to say that debates would be so much easier if people I disagree with would just have the humility to admit that they are wrong.

But back to Tamsin Edwards, who wrote

But whether we are in denial, lukewarm or concerned about global warming, the question really boils down to how we view uncertainty. If you agree with mainstream scientists, what would you be willing to do to reduce the predicted risks of substantial warming? And if you’re a lukewarmer, confident the Earth is not very sensitive, what would be at risk if you were wrong?

It seems to me that ‘lukewarmers’, to the extent that they are represented by Pielke and to a lesser extent by Betts and Edwards, still have a cultural, or spiritual home in The Gaurdian — or even at ATTP. But it is an unhappy home.

This is shown, I believe by taking a closer look at Edward’s naive definition of the climate debate’s fundamental axis, that denial-lukwarmism-concern are reflected by one’s estimation of likely warming impact. As I wrote at Bishop Hill in the comments,

—

Here Tamsin should admit that this is ‘ideology’ or politics — the precautionary principle, reformulated — not straightforward risk analysis.

It follows that if you take a view of ‘nature’ which is fragile, exists in ‘balance’, and provides for human society, any interruption to the imagined Order of the world will be catastrophic — a contemporary, secular reading of the The Fall.

If on the other hand you take the view that human society is (or can be) more dependent on itself than dependent on natural processes, which don’t exist in quite such a perilous state as has been imagined, the perturbations caused by human society are of lesser consequence.

I can agree with a ‘mainstream scientist’ that his predictions (such as they are) are plausible without committing to the idea that substantial warming creates uniquely challenging risks. Conversely, the green view used to hold (i.e. Greens used to be frank about it) that tiny perturbations can precipitate huge changes in the natural environment. One can be wrong about low climate sensitivity, but still be able to face the societal and technical challenges this would imply, even if that meant, 500 years hence, abandoning London to the sea (or rescuing it through some form of engineering). After all, human life thrives across a vast range of environmental conditions.

There is the question of the sensitivity of climate to CO2, and there is the question of society’s sensitivity to climate. They should not be conflated. Conflating them is to presuppose the green view of nature in balance, and the perfect form of social organisation reflecting that balance.

If the notion of risk is still important, Tamsin’s question to the lukewarmer and mainstream scientist can be turned inside out. What are the risks of holding with the view that society is dependent on ‘balance’ with natural processes? And what are the risks of believing that human society is largely self-dependent. Added to these risk calculations are moral and political questions — is a society that models itself on ‘nature’ better than one that models itself on its own measure? I don’t believe Tamsin’s questions — nor any implications of climate science — make any sense until those questions have been answered. That’s not to say that even the radically human-centric view of the debate wouldn’t choose some form of mitigation, but it does suggest that mitigation at all costs, and in the political form of that the agenda currently takes would likely be off the cards, so to speak, and would be seen for the deeply regressive tendency that it is.

—

It seems to me that debates about the environment, and climate in particular rest on more than one axis. Of course, there is this index of sensitivity, which is important.

But then there is the question of the degree to which human society is dependent for any given stage of development, on natural processes, or ‘stability’. And this is arguably just as important.

Then there is the question, related to the first and second, about the necessity of organising public life around the principles seemingly understood from environmental/climate science.

I don’t believe that the first axis is the only axis in this debate. As I describe above, one could take a high position with respect to climate sensitivity, but have a high estimation of human society and humans as individuals, to determine that the benefits of industrial society are worth bearings the cost-consequences for, on economic, moral, or political bases. Moreover, I have had many arguments with people of an alarmist bent in which it has become obvious that they are keener on a society organised around the authority of climate science than they are keen on understanding precisely what climate science has determined, which is to say that such a position is nakedly ‘ideological’, yet owes very little of its understanding to science. And on the other hand, I have argued with just as many putative ‘deniers’ who would seem to accept a great deal of state control of their lives, should it be discovered that indeed the climate is changing as dramatically as been claimed, such is the limitation of pure climate scepticism.

Over at TheLukewarmer’s Way, Thomas Fuller enumerates the things, per Lucia, that lukewarmers disagree with others about:

“Lukewarmer disagree with those who:

1) Believe CO2 has no net warming effect.

2) Believe the warming effect is so small that any observed rise in measured global temperature is 100% due to natural causes.

3) Believe the measured global temperature rise purely or mostly a result of “fiddling”.

4) Believe the world is more likely to cool over the next 100 years than warm.”

And for:

* lukewarmers believe ECS is on the lower end of the IPCC AR4 range […]

* … recognize the magnitude of the temperature change matters as does the rate of change.[…]

* … think it’s important for the estimates of ECS used in economic models that are used to guide policy to not be biased by things like using inapproriate priors […]

* … disagree with the rhetoric that suggests that we must all focus on the high end of ECS […]

This would seem to claim that lukewarmism is qualitatively different from scepticism and ‘warmism’, not merely a position taken after triangulating between having ones cake and eating it. But that appears to be the implication, unfortunately. And this is perhaps the limitation of honest brokerage, lukewarmism and the new manifesto offered by the ‘ecomodernists’.

As I pointed out here in an earlier discussion about words…

I find it hard to fault Pielke, Nerlich or Curry’s thinking on most things. But I wonder what use there is in an endless taxonomy of agents in the climate debate, and ideas about configuring effective relationships between science and governance.

Would even an honest broker have ever been able to resist eugenics and neomalthusianism? Could being objective about the evidence, and helping politicians consider the evidence have stopped the ‘limits to growth’ thesis from developing its toxic hold over (and against) the development agenda? Could public engagement have stopped 20th Century scientific racism?

The following may sound shrill, and lean towards a reductio-ad-Hitlerum argument. But notice that, even though we all now know that the racial science of the early 20th Century was political, not even the Royal Society is so aware of the difference between science and ‘ideology’ that it recognises mid 20th Century malthusianism as a racist doctrine and Paul Ehrlich as a nasty racist. The Royal Society gives Ehrlich awards instead, salvages his failed prophecies, and re-animates them to increase their own leverage in political debates about the environment. The task in front of the honest broker is bigger than he realises: it’s him versus some serious institutional muscle.

Just a few years south of Rio Declaration’s fourth decade, I would argue, is a little bit late to start worrying about merely fixing the relationship between science and policy-making, such that only the best science gets through, untrammelled by alarmism — denial was never admitted to the debate anyway. If lukewarmism really is about merely fixing this relationship after locating some sensible middle ground, it is hopeless. It is not equal to the task of understanding why the environment in general and climate in particular have become encompassing frameworks for understanding the world and things within it such as poverty, war, inequality, and decline in the ‘general sense of wellbeing’, and as such is not equal to the task of understanding what impedes transparent dialogue between science and policymaking. It is not enough to merely say that we should use ‘good science’; the reason why policymakers have sought the moral authority of science needs to be understood, before we can say what is good science and what is not. And it is not enough to produce glossy manifestos, aiming to put policy-making and the natural science on the right track. Until the reasons why alarmist manifestos and the models that underpin them were able to thrive are understood, there can be no sensible manifesto.

In other words, if ‘lukewarmism’ tries to define itself as anything other than merely an attitude towards debate — for instance by attaching itself to an estimate of climate sensitivity — then it is as problematic as outright denial or rabid alarmism. I always thought this was what was meant by ‘lukewarm’, and that the middleground estimation of climate sensitivity was the consequence of not being invested either in ideas about scientific fraud or in particular political agendas. It seems that many lukewarmers are, after all, refugees from the green camp, displaced — or even expelled by the shrill rhetoric of so many Lewandowskys and Oreskes — by alarmism, but not really willing to ask why they are in exile.

Of course, many (but not all) lukewarmers do ask such questions. But perhaps ‘lukewarm’ doesn’t describe very much at all, except where a position exists in relation to another. There’s little point trying to define lukewarmism for all values of alarmism, or for all values of denial, since the debate is fluid, and moves on. New issues emerge, such as the pause, or ocean acidification, or climategate, or Himalayagate. Each creates new challenges for the putative camp in question to explain the development. Giving things names, more often than not, is an attempt to keep the debate frozen.

There is a quote somewhere, which I have lost: once you give something a name, you don’t have to argue with it. This is the tactic followed by Lewandowsky, Oreskes et al. By suggesting that there is a phenomenon of denial… And now lukewarmism in the form of reflection on the hiatus, it becomes an object of study, rather than an analysis or judgement in its own right. Lewandowsky and Orsekes no longer need to defer to climate science — nor even climate scientists — they simply need to say that science is vulnerable to some force which is greater than it. Deniers are vulnerable to ‘conspiracy ideation’, and climate scientists are vulnerable to deniers’ conspiracies to undermine certainty with doubt. No deniers, sceptics, lukewarmers or even climate scientists are allowed to have found the data on the hiatus interesting in its own right. Don’t take my word for it, ask Lewandowsky et al.

—

UPDATE.

Roger Pielke Jr. tweets that he rejects the term ‘lukewarmer’, and adds: “Distinguishing political perspectives according to ECS is antithetical to robust policy & inclusive politics”.

I would again add that I think the term isn’t meaningful, so I don’t mean a lot by it. My apologies to Pielke, nonetheless. This is the problem with labels. By referring to him as a ‘lukewarmer’ I was not referring to his estimates of sensitivity, but as I point out later, an approach to debate, contra those who are hostile to it, which holds that it is essential.

Wake Up and Smell the Coffee!

Another day, another apocalyptic story in the Guardian…

Coffee catastrophe beckons as climate change threatens arabica plant

Study warns that rising temperatures pose serious threat to global coffee market, potentially affecting livelihoods of small farmers and pushing up prices

Oh no! Not Coffee! HOWWOULDWEGETANYTHIGNDONEWITHOUTCOFEE?!

Coffee, as we all now know, is grown by poor people. And, as we all know, climate change is worse for the poor. Never mind that environmentalists — who claim to care for the poor — hate coffee shops (unless they’re in Amsterdam), and hate global trade and hate the vehicles that global trade depends on, and hate even more the fuels that make advanced agriculture and global shipping possible…

Cultivation of the arabica coffee plant, staple of daily caffeine fixes and economic lifeline for millions of small farmers, is under threat from climate change as rising temperatures and new rainfall patterns limit the areas where it can be grown, researchers have warned.

This is surely a disaster.

With global temperatures forecast to increase by 2C-2.5C over the next few decades, a report predicts that some of the major coffee producing countries will suffer serious losses, reducing supplies and driving up prices.

2.5 degrees over the next few decades? Really? Over the course of my coffee-drinking career — i.e. my adult life — the globe has warmed by approximately no degrees centigrade. But let’s not worry about that right now. What exactly is the claim?

The joint study, published by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) under the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), models the global suitability of arabica cultivation to see how production will be affected in 2050.

It predicts that Brazil, Vietnam, Indonesia and Colombia – which between them produce 65% of the global market share of arabica – will find themselves experiencing severe losses unless steps are taken to change the genetics of the crops as well as the manner and areas in which it is grown.

Well, we can all agree that adaptation is a Good Thing, and is likely a good way of responding to climate change. But there’s adaptation and there’s adaptation. Most adaptation is a decision that can be taken at the level of the farm. The implication of the study, however, is that coffee growers will have to move ever upwards to cope with the changing climate, demanding the intervention of national and global carbon bureaucracies.

But is this true? What’s the evidence for it?

It doesn’t exist in the statistics relating to the production of coffee provided by the UN. Here is a chart showing coffee production in the countries named by the Guardian in the passage above, and for the world total.

World coffee production has doubled since 1980. Coffee production has tripled in Brazil since 1995, and output is less volatile. Vietnam has emerged as a coffee superpower in just two decades. Indonesia’s coffee production has shown slow, but steady and sure growth. This picture is hard to marry with the story that coffee production is getting harder. The only loser here is Columbia, whose output seemed to peak in the early 1990s. For this we turn to Wikipedia for the standard explanation…

Regional climate change associated with global warming has caused Colombian coffee production to decline since 2006 from 12 million 132-pound bags, the standard measure, to 9 million bags in 2010. Average temperatures have risen 1 degree Celsius between 1980 to 2010, with average precipitation increasing 25 percent in the last few years, disrupting the specific climatic requirements of the Coffea arabica bean.[13]

Well that’s one explanation for Colombia’s coffee production decline. But there are at least two others… Fair trade organisation, Equal Exchange offer this account:

The global coffee [price] crisis hit Colombia’s small producers hard. Twenty-three percent of producers were not meeting production costs in the nineteen nineties. The affect on producer families varied by region, but overall the crisis sent people further into poverty and debt. Malnutrition among small children in farm families went up significantly, while coffee production across the country fell 44% as farmers could no longer afford to harvest and process their crops. Many farmers were forced to migrate for work in urban areas leading to increased unemployment and more poverty.

The article is not without its own tendency to sustainabollocks. And this journal article offers a third perspective, but which it also attempts to link to climate change…

Coffee rust is a leaf disease caused by the fungus, Hemileia vastatrix. Coffee rust epidemics, with intensities higher than previously observed, have affected a number of countries including: Colombia, from 2008 to 2011; Central America and Mexico, in 2012–13; and Peru and Ecuador in 2013. There are many contributing factors to the onset of these epidemics e.g. the state of the economy, crop management decisions and the prevailing weather, and many resulting impacts e.g. on production, on farmers’ and labourers’ income and livelihood, and on food security. Production has been considerably reduced in Colombia (by 31 % on average during the epidemic years compared with 2007) and Central America (by 16 % in 2013 compared with 2011–12 and by 10 % in 2013–14 compared with 2012–13). These reductions have had direct impacts on the livelihoods of thousands of smallholders and harvesters. For these populations, particularly in Central America, coffee is often the only source of income used to buy food and supplies for the cultivation of basic grains. As a result, the coffee rust epidemic has had indirect impacts on food security. The main drivers of these epidemics are economic and meteorological. All the intense epidemics experienced during the last 37 years in Central America and Colombia were concurrent with low coffee profitability periods due to coffee price declines, as was the case in the 2012–13 Central American epidemic, or due to increases in input costs, as in the 2008–11 Colombian epidemics. Low profitability led to suboptimal coffee management, which resulted in increased plant vulnerability to pests and diseases. A common factor in the recent Colombian and Central American epidemics was a reduction in the diurnal thermal amplitude, with higher minimum/lower maximum temperatures (+0.1 °C/-0.5 °C on average during 2008–2011 compared to a low coffee rust incidence period, 1991–1994, in Chinchiná, Colombia; +0.9 °C/-1.2 °C on average in 2012 compared with prevailing climate, in 1224 farms from Guatemala). This likely decreased the latency period of the disease. These epidemics should be considered as a warning for the future, as they were enhanced by weather conditions consistent with climate change. Appropriate actions need to be taken in the near future to address this issue including: the development and establishment of resistant coffee cultivars; the creation of early warning systems; the design of crop management systems adapted to climate change and to pest and disease threats; and socio-economic solutions such as training and organisational strengthening.

But the link between climate change — whether it be natural or anthropogenic — and reduced coffee bean production is speculation. The research only suggests it as a ‘likely’ part-cause of an epidemic, given relatively modest changes in temperature extremes, which itself had a much more profound effect on production, which was again much more likely an economic consequence — low price and poverty. Let us not forget that greens are hostile to interventions which could have prevented the disease — pesticides — and campaign to abolish their use, and have persuaded Fair Trade organisations to make ‘sustainability’ a condition of trade. In other words, it is not implausible that the demands of ‘sustainability’ could have caused the very problem which its advocates now attribute to climate change.

A broader picture of climate change’s effect on coffee production can be gained by looking at each country’s yield.

Again, we can see that the story of environmental decline doesn’t fit with the statistics. We can see no signal corresponding to climate change in any country except Colombia, which we have an explanation for. Moreover, in the case of Vietnam, where we can see a dramatic shift in yield between the late 1990s and mid 2000s, which the environmentalist might be tempted to explain as the consequence of climate change. But he would be wrong. The producer price of coffee fell between 1997 and 2004, before rising again. As this graph of Colombian production statistics shows. (The data for producer prices in Vietnam do not exist over this time range).

Economics accounts for changes in production yield much better than climate. When the price is low, the yield is low.

The Guardian article continues, quoting one of the study’s authors…

“If you look at the countries that will lose out most, they’re countries like El Salvador, Nicaragua and Honduras, which have steep hills and volcanoes,” he said. “As you move up, there’s less and less area. But if you look at some South American or east African countries, you have plateaus and a lot of areas at higher altitudes, so they will lose much less.”

So do these countries show any sign of being vulnerable to climate change yet? Here are the production and yield stats for those countries.

We can see coffee production increase in Honduras and Nicaragua, and yield increase in Honduras, with wobbly increase for yield in Nicaragua. The case of El Salvador is very different. Coffee production fell, and has not recovered since 1979, and its yield has fallen since 1969. Is this the result of climate change?

No. In the cases of both Nicaragua and El Salvador, conflict much better explains changes in production statistics than climate change. In Nicaragua, civil war affects production through the 1980s, which was amplified by US sanctions, and the reduction in yield from the late 1990s through the mid 200s is explained by the lower prices that affected Vietnam. Civil war affected El Salvador through the 1980s, also, from which the El Salvadorian economy has not recovered .

The report‘s abstract reads as follows…

Regional studies have shown that climate change will affect climatic suitability for Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) within current regions of production. Increases in temperature and changes in precipitation patterns will decrease yield, reduce quality and increase pest and disease pressure. This is the first global study on the impact of climate change on suitability to grow Arabica coffee. We modeled the global distribution of Arabica coffee under changes in climatic suitability by 2050s as projected by 21 global circulation models. The results suggest decreased areas suitable for Arabica coffee in Mesoamerica at lower altitudes. In South America close to the equator higher elevations could benefit, but higher latitudes lose suitability. Coffee regions in Ethiopia and Kenya are projected to become more suitable but those in India and Vietnam to become less suitable. Globally, we predict decreases in climatic suitability at lower altitudes and high latitudes, which may shift production among the major regions that produce Arabica coffee.

This seems to me to reproduce the same old trick, of plugging in worst-case scenario projections into modelled assumptions of sensitivity of this-or-that to climate, to reveal, hey-presto, a sound prediction of what life will be like a few decades hence. Yet we can see that climate has had very little impact on agricultural production, if any negative impact at all. And we can see that economics plays a much bigger role in agricultural production than any environmental effect.

These kind of studies claim to want to protect the interests of producers. Yet their futures don’t seem to be at all dependent on the interventions of climate bureaucracies, if there is any lesson to be had from the past. The weather is simply the weather, whereas price volatility and conflict are the real enemies of farmers in poorer economies. Wealth allows for the proper management of crops, as well as adaptation to any kind of weather. The study does not appear to have attempted to isolate climate and its Nth-order effects from economic effects and conflict in its estimation of coffee-production’s sensitivity to climate. Why not?

This doesn’t exclude the possibility, of course, that dramatic shifts in climate could create problems for coffee producers. Of course it could. Yet even extreme weather, such as that which caused widespread damage in coffee-producing economies in the late 1990s as a result of El Nino don’t seem to have affected coffee production. In fact, the price of coffee fell following the 1997-8 El Nino, no doubt amplifying the consequences for recovery.

To link agricultural production and climate change in this way — as seems to be the greens’ want — is to make instrumental use of the plight of producers in poorer economies. It does not aim to intervene in any way that would improve their condition. The purpose is to inflate an already engorged bureaucracy and add to its powers. A genuine discussion about how to improve the conditions of producers in poorer economies would be about how best to allow a situation in which fewer farmers produced more goods, leaving more people to produce the machines and chemicals those wealthier farmers would use in their work, the other services they would use in their lives, and the books, films and music they would use in their leisure time.

But bloated, ambitious green bureaucracies and their academic organs like the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security, which produced this report don’t want such lifestyles for poorer producers.

No single research institution working alone can address the critically important issues of global climate change, agriculture and food security. The CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) will address the increasing challenge of global warming and declining food security on agricultural practices, policies and measures through a strategic collaboration between CGIAR and Future Earth.

Food security is not an ‘increasing challenge’. It is a challenge which has reduced dramatically over just the timespan of anthropogenic global warming. More people have more access to better quality food than ever before. Only in the minds of bureaucrats and climate impact models is the world a worse place than it ever has been. The reasons for this are obvious.

Greens Whinge About Consensus

The looming UK general election has so far been a contest of the lowest possible expectations. It is a difficult election to get excited about. But one group seems to feel especially hurt at being left out of the debate, with their favourite subject having taken a back seat to promises about lowering the cost of living, creating jobs and making tax-dodgers pay their fair share.

Over at Business Green — the on-line trade magazine for subsidy-junkies — we’re told that

Election campaign ‘failing to address’ green energy concerns

Said subsidy-junkies had polled themselves, and found them disillusioned with the substance of the election debates. The Renewable Energy Association (REA) asked its members if they ‘feel that the political parties are addressing the needs of the renewable energy {sic} during this election campaign’. 95% of 136 respondents said they did not. It seems that 1 in 20 turkeys voted for Christmas.

The Green Party was viewed as the party that would be ‘best for the renewable energy industry’ (29%) with the Liberal Democrats seen as the next best.

Members were less optimistic about the two parties most likely to form a government after the election. Nearly a fifth (18%) of respondents believed that the industry would be in the best hands under Labour, whereas the Conservatives received the support of 15%.

No doubt industries and the individuals within them have their favourites. But isn’t it odd for a particular industry to imagine itself and its favourite topics as deserving special status. There is much hand-wringing about large energy interests getting involved in politics — especially in the USA — but Business Green and the REA seem somewhat unashamed to admit that their own interests lie in particular election outcomes. When fossil fuel companies appear to expect special treatment from politics, green organisations and journalists are the very first to complain. And nobody can say that there hasn’t been emphasis on green energy — including the closure of many fossil fuel power plants, and much green legislation — in the UK over the last two parliamentary terms.

The green sector and green organisations have enjoyed much privilege. Yet Green Party and Climate Outreach & Information Network activist and part time academic psychologist, Adam Corner complained in the Guardian that

We need our leaders to speak out on climate change, not stay silent

The less that political, community and business leaders talk about climate change, the more scope there is for scepticism to emerge

There is plenty of stuff in the manifestos, Corner observed, but not in the debate.

So while there appears to be a robust political consensus around the importance of climate change, it is a silent consensus – which from the point of view of public engagement, may as well not be a consensus at all.

And out comes the cod psychology…

One important factor known to influence public opinion is whether elite groups (such as politicians and other public figures) give positive or negative cues on climate change. What our political leaders say about climate change matters – especially if they say nothing at all.

But perhaps one reason for this ‘silence’ is that political parties and their machines have decided that the public aren’t receptive to climate change, no matter what Corner’s research leads him to believe about ‘positive messaging’. After all, when people are more worried about jobs, the cost of living, the economy, health, and taxation, to bang on about climate change might look somewhat callous. Moreover, it risks giving a hostage to fortune, with UKIP being the only party willing to criticise the prevailing political consensus, and which has rapidly absorbed working and middle class voters alienated by the Labour and Conservative parties.

Even the Green Party has chosen to emphasise its social justice agenda rather than the environment. Its manifesto promises to ‘end austerity’ and create a million public service jobs paid for by a new ‘Robin Hood’ wealth tax and create a £10/hour minimum wage, protect the NHS from privatisation and increase spending on mental health, before it gets round to tackling climate change.

The climate simply hasn’t been the rousing chorus that environmentalists want it to be.

But another reason for the ‘silence’ is the fact of consensus politics creating a democratic deficit. To expose the political consensus to debate would be to challenge its very foundations, to test the public’s sympathy for it. This is simply too risky.

The cross party consensus on climate change was renewed for this election in a deal brokered by the Green Alliance.